NOMA Puts People in Ralston Crawford's Buildings

The portraits that seem like red herrings in NOMA's Ralston Crawford show add an important human element.

When you enter "Ralston Crawford and Jazz," a show currently on display at the New Orleans Museum of Art, it's important to remember that it is not in chronological order. The first rooms present the photographer's documentation of New Orleans' jazz life in the 1950s during the Jazz Renaissance, and because we see them first, it's tempting to think of them as in some way leading to the starker cityscape photos, works that are more about the interplay of forms and light than the actual buildings depicted. Or, we see them as abandoned for more serious artistic pursuits, but Crawford's portrait work and his more architectural work happened at the same time, and after looking at some of the building shots, you can walk back to the portraits and look past the details of the faces to see the same concerns with form and light at play.

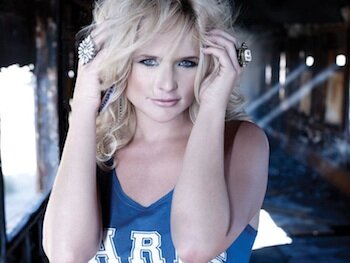

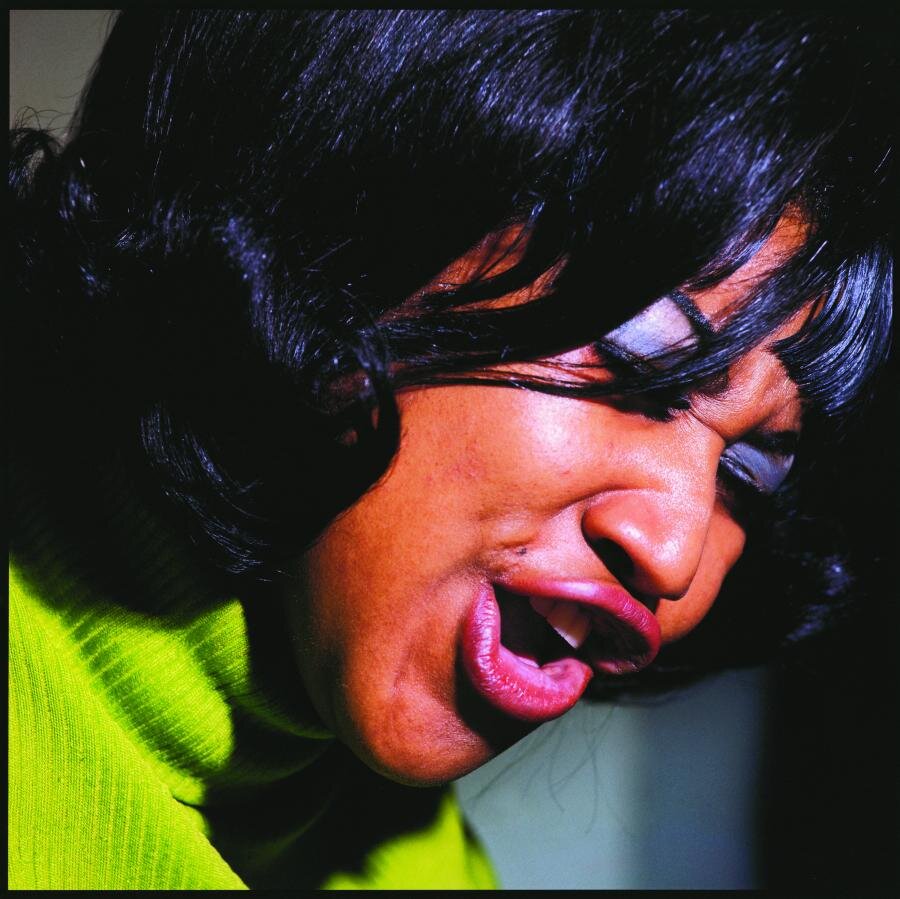

Don't look past the faces too quickly, though. New Orleans jazz was one of the photographer's great loves, and these are the people whose work drew him again and again back to New Orleans. There's an obvious affection in these portraits that doesn't show in his other, more dispassionate work, and the comfort on the faces of his subjects says that he was more than just their photographer. They'd developed relationships. These portraits are also a reminder of how time will treat most of us. These players were likely significant enough to merit his attention, but only a handful of names have endured beyond traditional jazz aficionados - Billie and DeDe Pierce, Harold Dejan, Frog Joseph, Oscar "Papa" Celestin. The others are now a collection of colorful names that mattered in their moment.

The portraits are the news in the show, and the jazz connection suggests artistic values that might not have immediately suggested themselves in his better-known modernist photography. The shot the city as a series of shapes more than actual places, and was fascinated by textures that architectural details provided. The ultimate expression of this is "The River," a 20-minute movie during which Crawford's stationary camera captures a static scene - a chain-link fence railing, the dark interior of the ferry with midday light streaming in - and lets the changing exterior in the background animate the work. In the process, the details of image genuinely become secondary to the contrasting shapes, light and textures that cross his lens.

Crawford's art depicted the growth of an industrialized America, one in physical, technological and architectural flux, and his work reflected an essential positivity toward accomplishment. His photos and prints present a depopulated vision of America though, as people are conspicuously rare in them. The success of "Ralston Crawford and Jazz" is that it puts people in his world.

"Ralston Crawford and Jazz" will be on display until October 14.