American Idol After Tyler and J-Lo

This morning I tried to interview American Idol hopefuls that are auditioning today at the New Orleans Arena, but with no luck. I wanted to see if I could gauge their levels of delusion, but to the producers' credit, they had people inside and out of the punishing sun today. Unfortunately, that also meant that they were a safe distance from wiseguys like me.

My trip seemed to me a little after the fact even as I was making it. Since Carrie Underwood, Idol hasn't produced an idol, and last season's Phil Phillips joins the recent string of winning WGWGs - "white guy with guitar" in Idol shorthand - who seem bound for the cut-out bin, if such things still exist. Even long-time Idol tracker and Friend-of-Milk critic Ann Powers bailed on last season:

Great television rivets us when its narrative, unfolding over time, reflects and heightens a particular kind of experience. Cheers did it for bar life. Friends did it for, well, friends. American Idol did it for the dream of pop, exposing the starmaking process and even allowing fans to become part of it. Just as online music began pushing the corporate music industry toward a radical new reality, American Idol laid its essence bare, and let average people (contestants and voting viewers) taste it.

But now, Idol and the programs that emulate it have played out all the stories mainstream music once offered. The ingenue rising from innocent obscurity; the contender getting another try; the marginalized person pushing her way into the center — these scripts have been exhausted. The songs aren't the only things repeating; the basic plotlines of each series have been exhausted and feel increasingly irrelevant.

Idol has always had a fundamental complicating factor - it's an audience-voted talent show and a months-long marketing process for an artist who will be managed by the show's production company, with that person's music coming out on the label of the participating record exec - Clive Davis' J Records for years, and now Jimmy Iovine's Interscope. All of the commentary and analysis is grooming; all the voting is market research.

That makes the show a way to read the music industry's tea leaves. One season, Simon Cowell rips a guy for singing country, but a year later he celebrates Carrie Underwood because country was too big of a market to miss. Chris Daughtry lasted longer than he might have in previous seasons in recognition of the hard rock audience, and the army of WGWGs followed the success of the Sons of Dave Matthews - Gavin DeGraw, Jason Mraz, and so on.

But the research has been misleading because the votes are deceptive, and not in the Vote Sanjaya way. Reports are that the leading voters are young and older women, and you can look at the WGWGs and suspect that the women vote not for the person whose music they most want to buy but for the singer they like as a person. Television has always been about likeability, and Taylor Hicks, David Cook, Kris Allen, Lee DeWyze and Scotty McCreery were all nice young boys - guys you'd be okay with your daughter dating if you're a mom, and guys who'd go out with you but not pressure you to do you-know if you're an early teen. Unfortunately, the bone pile of failed idols says that people don't want to buy those people's music.

That has left the show with an Emperor's New Clothes quality as year after year, it presents itself a search for the superstar that its track record says it won't produce. The pomp seems undeserved and the critical acclaim from the judges rings phony, even when it's accurate. Without a compelling central narrative - the making of a star - the show has become about the judges and their celebrity. The Voice judges (Christina Aguilera, Cee Lo Green, Adam Levine and Blake Shelton) are more about the present than Steven Tyler, Jennifer Lopez, or any of the names bandied about as their possible replacements, and The Sing-Off's Ben Folds and Sara Bareilles are far more perceptive talking about music than any Idol judge since Simon Cowell, and he addressed who was marketable in the guise of talking about music.

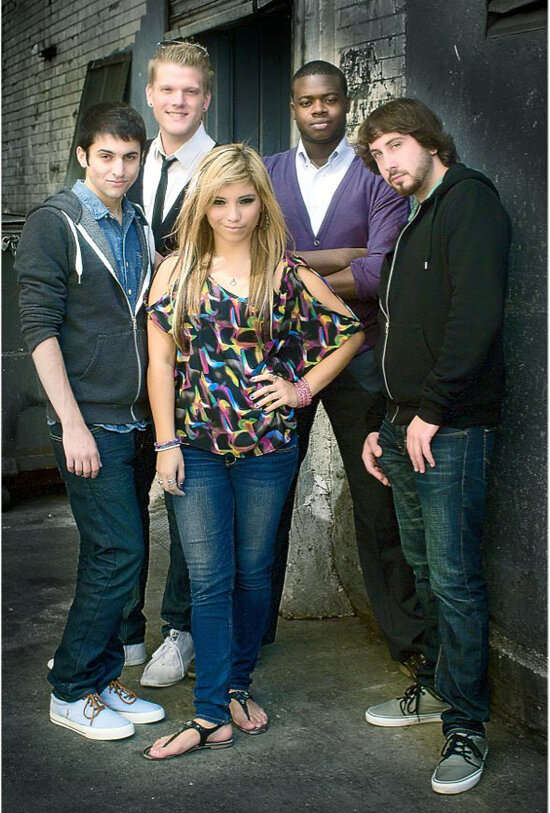

Still, I'll watch New Orleans week when it airs and hope that it is as good as Idol's last visit to New Orleans was. Two years ago, Jordan Dorsey, Lauren Turner and Jovany Barreto were all a part of that audition, and all made the top 24 before getting mowed down in the first cut - Dorsey and Barreto, I'd argue, on poor song choices that prevented them from being singers who could have gone a long way in the competition.

Is Idol competitor status something to aspire to? The New Orleans-based Barreto is bigger outside the country than he is here, where the show is associated with television and show business and the sort of artificiality audiences think they escape when they turn to music. But a handful of winners and runners-up have made careers for themselves - Fantasia, for instance, who recently rocked Essence - so maybe its all about how they use the platform. Which is why I wanted to talk to the hopefuls. Are they hoping for American Idol to make them, or are hoping to use American Idol to make themselves?

... and what are some of the costs associated with competing on American Idol?