Dapper Bruce Lafitte Shows His Roots in New NOMA Show

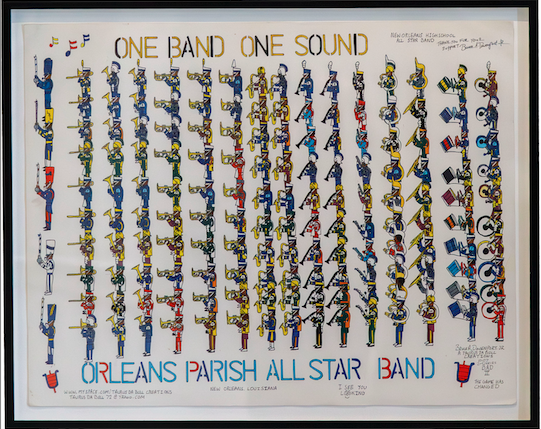

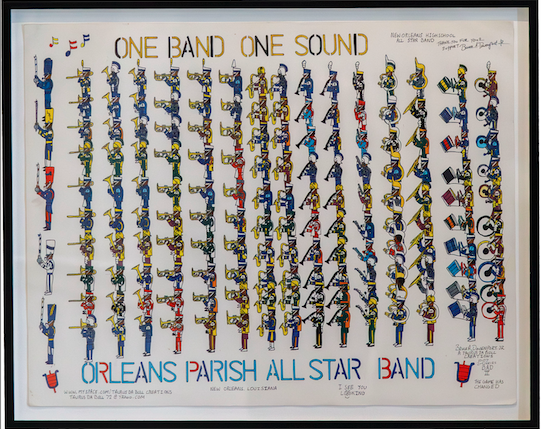

“Orleans Parish All Star Band” by Dapper Bruce Lafitte. Photo courtesy of the New Orleans Museum of Art.

The self-taught artist provides insight into his artistic progression and the world he grew up in.

Officially, the title of Dapper Bruce Lafitte’s show in the Great Hall at the New Orleans Museum of Art is “A Time Before Katrina.” An equally apt title would be “Becoming Bruce Lafitte.”

Most of the work in show dates back to Lafitte’s formative years as a self-taught artist, from 2006 to 2017. Marching high school bands, parades, and community gatherings are all depicted almost like schematic diagrams, and that tendency mutes any narrative tendencies he might have. Lafitte doesn’t depict moments of drama; instead, he shows us gatherings of Black people, and he remembers more than he illustrates the good and bad of those times. If you were there, you know.

But the show, which will up at NOMA through September 21, presents Lafitte’s journey as an artist. He’s self-taught, and when well-known champion of artists Diego Cortez saw his drawings and encouraged him, Lafitte made the first pieces in the show with a very business-like approach.

“After Katrina, I lost a lot of work,” he says. “The 2006 work, the 2007 work, it was just, Let me get some inventory up so I could show the world the art.”

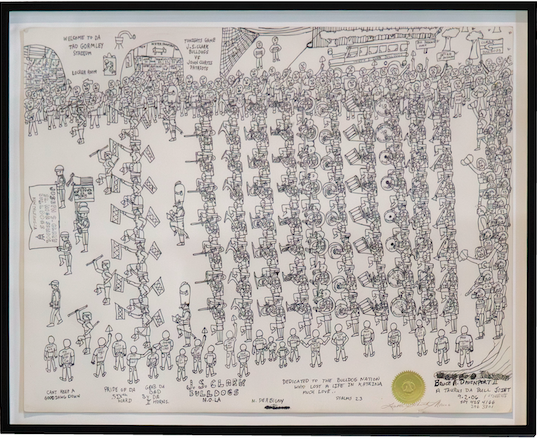

He views the early pieces in the show as “juvenile” and thinks of them as practice—“so I can get a better style,” Lafitte says. He made the early work using cheap paper and markers from Walmart, and part of the purpose of his 2006-2008 work was to test drive better paper and better markers to see how they worked.

Think of the show at NOMA as Lafitte’s proof of concept on display. You can see him experimenting with design-oriented compositions, first with marching bands in straight-ish lines, then on football fields and parade routes. He worked out how to imprint himself on pieces, mainly by incorporating touches drawn from hip-hop and the Black pop culture he grew up with. He incorporates handwritten text in his pieces like graffiti, but those bits of text speak directly to the viewer or the piece’s subjects. He started referring to his pieces as “Taurus Da Bull Creations,” a bit of branding and self-mythologizing along the lines of director Spike Lee referring to his movies as “a Spike Lee Joint.”

“Untitled (Welcome to Da Gormley Stadium), September 2, 2006” by Dapper Bruce Lafitte. Photo courtesy of the New Orleans Museum of Art.

The extremely geometric nature of his works remain one of the defining characteristics of his work, and he used a ruler early on to line up the rows of marching band members. Is that extreme geometric approach a way of imposing order on the unruly upbringing reflected his work? Lafitte says no, and that the boxes of images in the two larger 2017 pieces on display had practical origins.

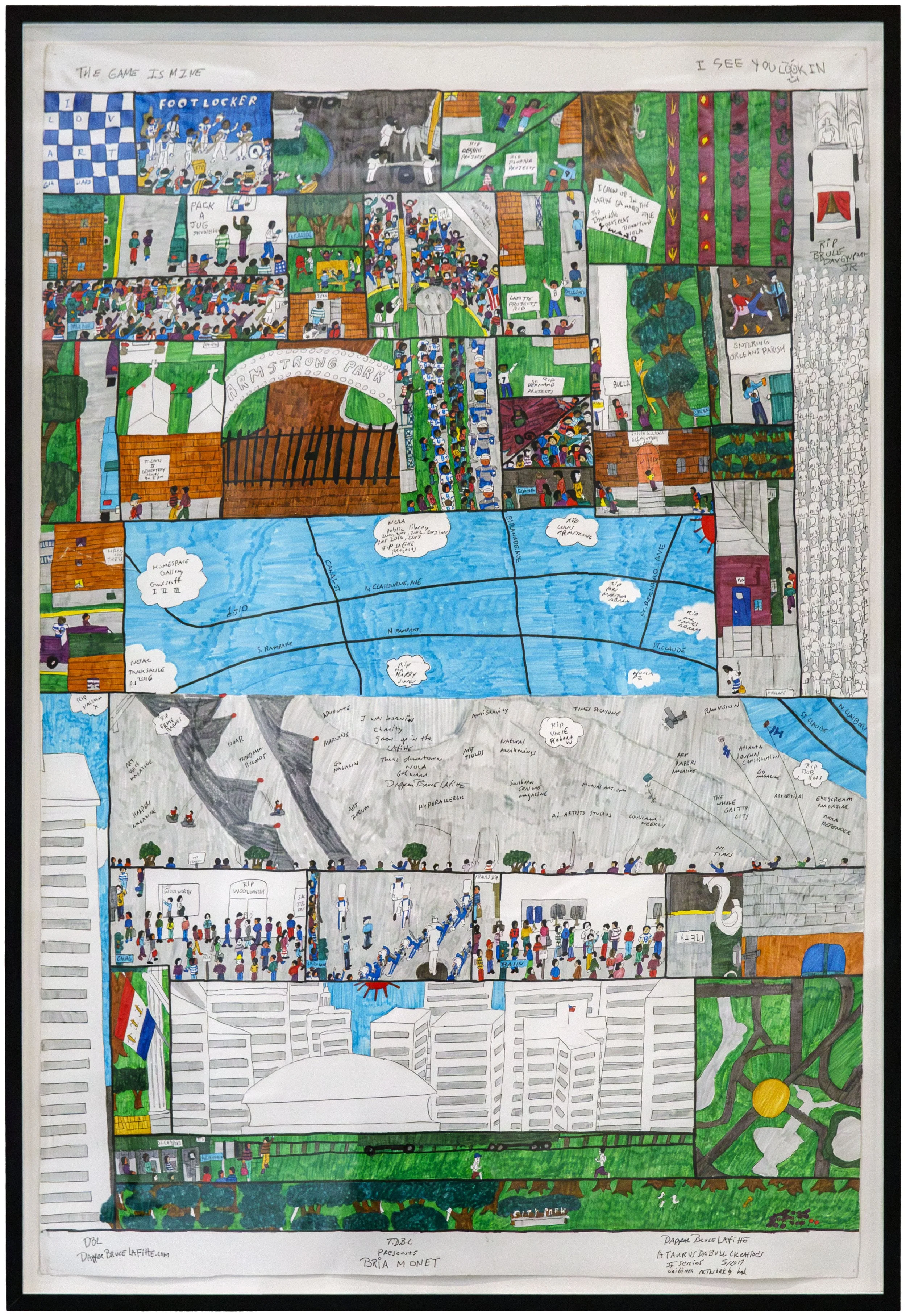

“When I watched Bob Ross, he’d explain to you why this mountain was here,” Lafitte says, referring to the famed television painting instructor. Lafitte came to think about his work like an architect would, with firm horizontal and vertical lines to give the piece structure. “That’s how I caught up with the artwork on the biggest scale. You put things in grids.”

The grid gave Lafitte a way to break the page into manageable chunks, and once established, he started at the bottom and worked his way up. “I build a foundation,” he explains. Lafitte thinks about the movement from box to box as movement in time much like comic strip panels, but because he starts at the bottom and changes scenes constantly, the pieces don’t read like comics. His larger works depict a short period of time in a specific space and how a community moves through it.

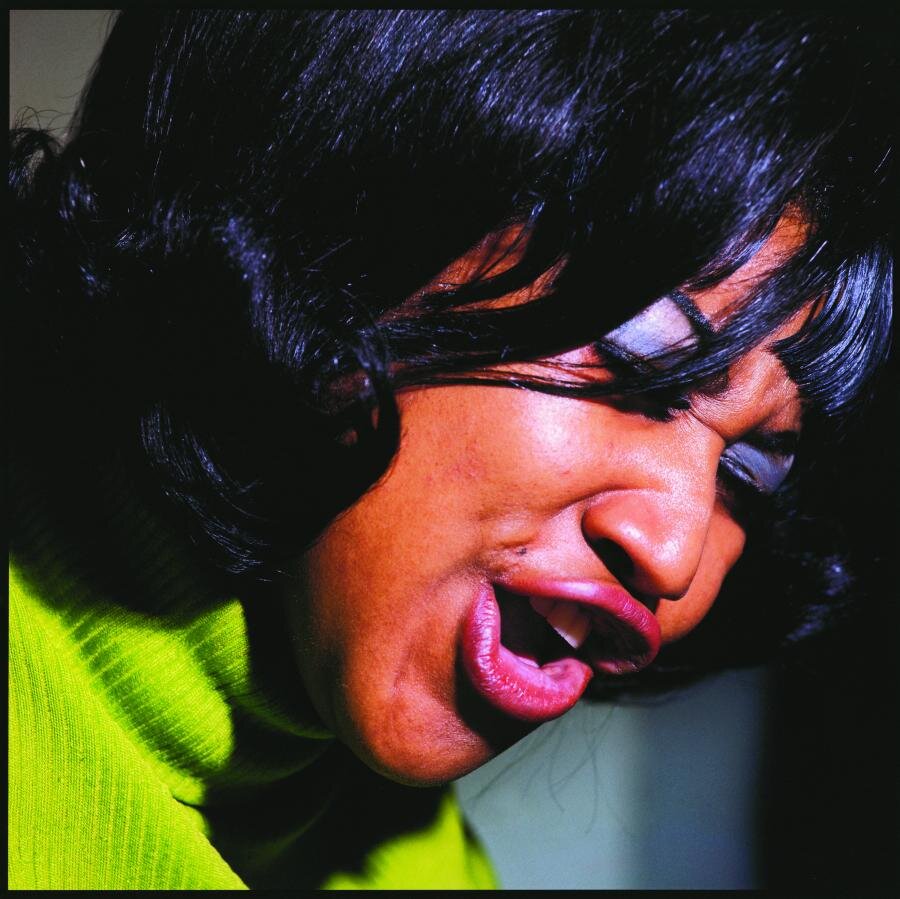

“TDBC Presents Bria Monet” by Dapper Bruce Lafitte. Photo courtesy of the New Orleans Museum of Art.

“A Time Before Katrina” does depict exactly what the title says. While it illustrate Lafitte’s journey as an artist, the content is firmly rooted in the late ’60s to the early ‘80s—a transformational time for him and the Ninth Ward projects. His school—Joseph S. Clark—shows up in the marching band pieces, but “their band fell off from 1986 to 2003,” he says. “In between those years, they didn’t have a band, so sometimes the work refers to when they had their better days, better years.”

That impulse toward better days runs through Lafitte’s work. “When crack came in, people didn’t want to be in a band,” he says. He wanted to draw attention to the bands and maybe inspire people to contribute to them and kids to join them.

“I wanted to show that someone cared about them.”

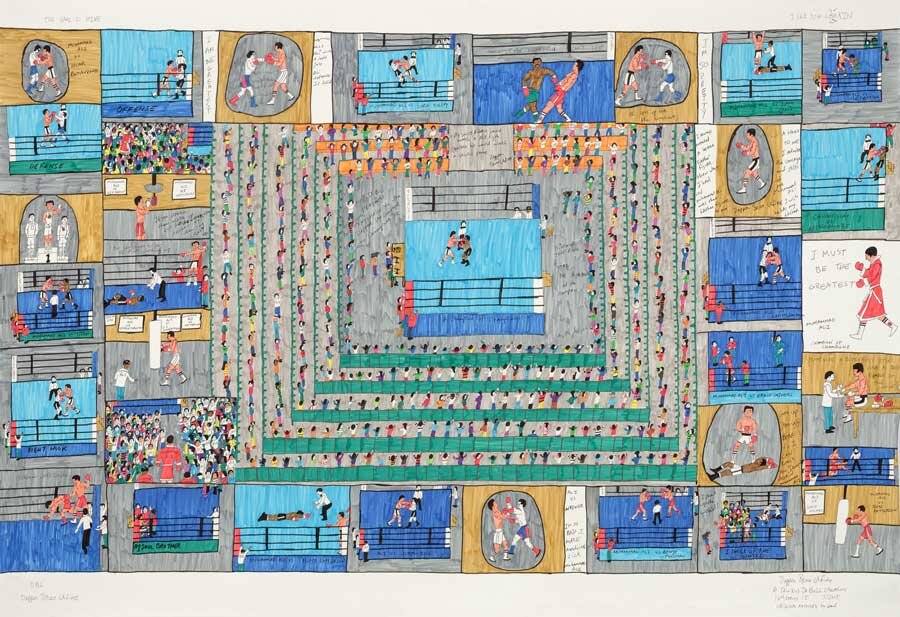

“TDBC Presents Na-Na 25” by Dapper Bruce Lafitte. Photo courtesy of the New Orleans Museum of Art.

His pieces from 2017 are closer in structure and theme to Lafitte’s current work as they take a larger, more ensemble approach to representing Black life in New Orleans. The pieces and ones he has made since reflect his love for the world that shaped him, and the people who shared those experiences see that in his work. After looking at “TDBC Presents Na-Na 25,” the diptych on the Desire Projects that’s new to this show, a woman asked Lafitte where he grew up. She grew up in Florida Projects and the piece clearly signaled to her that they share experiences. When Lafitte said his grandfather lived in Desire, she quickly asked if he drank at Club Desire.

“No, he was the older bars,” Lafitte said. “He wore a size 15 shoe and was, like, five-five. So he got along with everybody.”

“I always use Desire and Florida projects to represent New Orleans,” Lafitte continues. “The Ninth Ward projects. We had more things coming from those projects.” He recalls a time when Mardi Gras Indian chiefs, musicians, Black Panthers and even the drug dealers were helping to take care of their neighborhoods. “I show a time when bad stuff was going on, but you see the good result of it,” Lafitte says. “One time New Orleans was like that.”

I reviewed another Lafitte show and shot the video below in 2019.

Creator of My Spilt Milk and its spin-off Christmas music website and podcast, TwelveSongsOfChristmas.com.