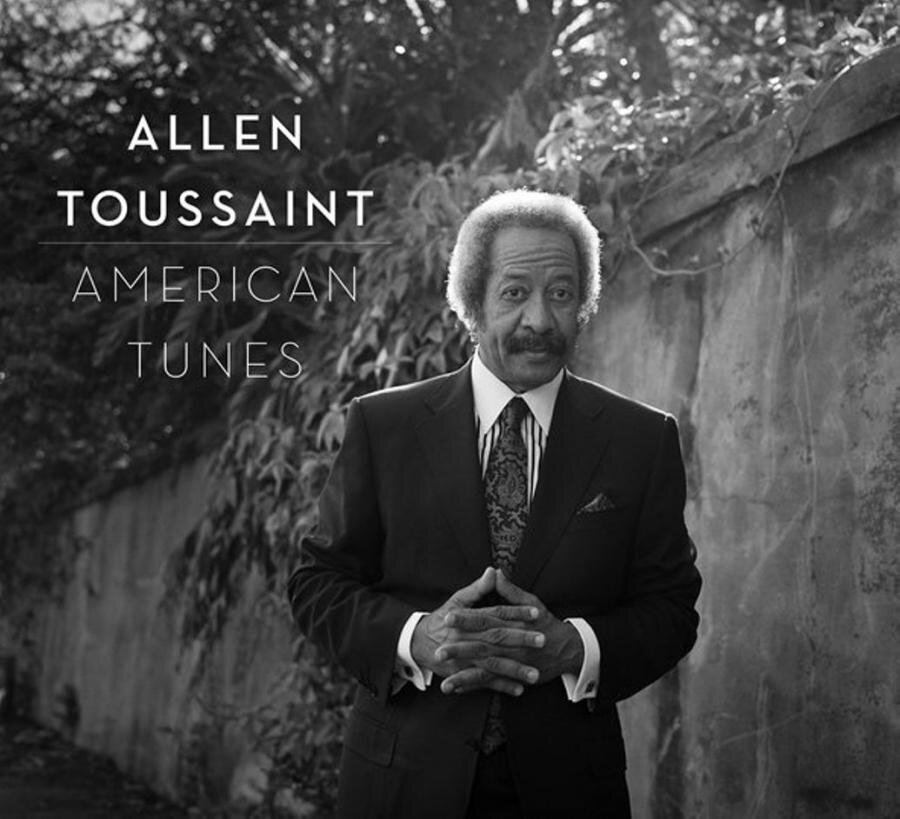

Friends Share Allen Toussaint Insights

A few final thoughts after the memorial for Allen Toussaint at The Orpheum Friday.

[Updated] Friday, the memorial for Allen Toussaint was, as Dr. John said, “appropriatin’.” It successfully touched on the breadth of Toussaint's acchievements and gave the audience a good sense of who he was as a man. His grace, dignity, and kindness were often talked about, but so was his sense of humor. Even the photos shown on a big screen during the visitation presented a life that took him from Lee Dorsey in someone's living room to Black Sabbath's Tony Iommi and Bill Ward at The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, At just over two hours, it bordered on too long, but it’s hard to imagine an artist and man whose life merited the time more. Others have written the play-by-play of the event at The Orpheum, but the presentations prompted a few final thoughts.

Elvis Costello’s memories of Allen were exactly what the moment needed. He was a valuable reminder of the way Toussaint was viewed in England, where he was still revered as a hitmaker—particularly with Lee Dorsey—in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, well after American top 40 radio had moved on from New Orleans R&B. When Costello talked about touring with Toussaint after the release of The River in Reverse, he remembered him with the sort of humor we have for the people we care about—something other speakers rarely did. “I only recall seeing Allen take off his jacket once,” Costello said, then told the story of coming to a venue in Japan where the crew was buzzing because Toussaint wasn’t wearing a jacket. When Costello laid eyes on him, he saw Toussaint was wearing “a perfect powder blue tracksuit. The stripes on the side lined up perfectly.”

He also remembered Toussaint’s generosity and quick wisdom when he offered to join Costello on a visit to wounded veterans from Iraq. Many clearly were too young to know either artist’s work, but Toussaint, remembering his days in the service, defused any awkwardness when he asked, “What’s your MOS?” (military occupational specialty) and started conversations with soldiers in a way that neither’s celebrity status could.

Boz Scaggs remembered recently seeing Toussaint performing “Southern Nights” in San Francisco—“a master class in mastery and class”—and perhaps because Scaggs had misplaced his remarks, he recalled Toussaint’s lengthy, storytelling intro to the song in lumbering, college essay-level detail to a roomful of people who'd seen and heard it before. Scaggs then remembered Bob Dylan saying that he wrote songs “for the people”—songs that spoke for them, songs that said what they couldn’t—and argued that Toussaint did the same. He then developed that thesis with an ad libbed Freshman Comp 101 rigor, but his performance of “What Do You Want the Girl to Do?” made the case better than paragraphs of explanation.

Part of Toussaint’s genius was to work in the common tongue—to write as people spoke. Every comedian had a mother-in-law joke when “Mother-In-Law” was written in 1961, and mother-in-laws were a staple on situation comedies of the day. Similarly, when Bonnie Raitt recorded “What Do You Want the Girl to Do” in 1975—and Scaggs did in ’76—it was as empathetic as any male songwriter was to women at the time. But watching four dudes—Scaggs backed by Jon Cleary and The Absolute Monster Gentlemen—mansplain how a woman thinks and feels Friday on the stage felt a little icky, particularly with its now-dated reference to the woman in question as a child. Still, it was a reminder of what a remarkable melodicist Toussaint was, and more importantly, the degree to which he was writing for the day in front of him and not posterity.

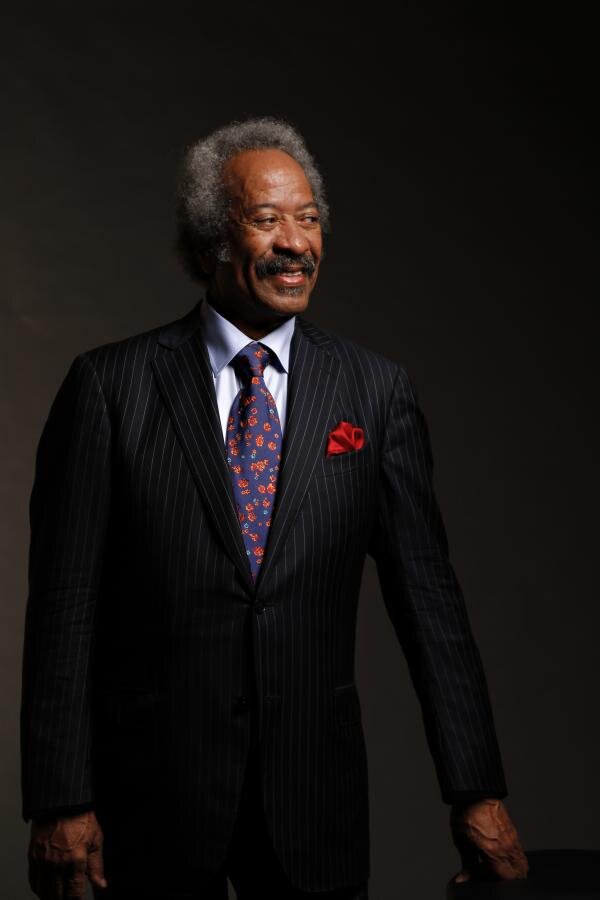

Finally, Joshua Feigenbaum, Toussaint’s friend and partner in NYNO Records, spoke at length about his friendship with Toussaint. He remembered walking through the French Quarter together, with Toussaint pointing out the musical significance of places you’d have to be a lifer to know. “Those walks through the Quarter could take a long time,” Feigenbaum said, because people would stop Toussaint to say hello and ask for a photo or autograph. For me, that is a part of the Toussaint story that shouldn’t be overlooked because for all of his musical gifts, it’s hard to imagine a musician that more people feel like they have a personal, first-hand connection with. Beyoncé and Bruce Springsteen have larger fan bases, greater fame, and I’m certain that a lot of people feel like they know Bey and Bruce. They feel their songs speak to them and for them, and that there’s a connection between them and their heroes. But those people haven’t shaken Beyoncé or Springsteen’s hand, or had friends shoot pictures of them together. They certainly didn’t feel enough license to stop Beyoncé or Springsteen if they saw them on the street to say hello.

Toussaint was always approachable and gracious to those who did. If he was ever put off by the gathering that formed to get a picture with him when he stopped, he never let it show.

Because of that, he was not simply a New Orleans great or a piece of rock ’n’ roll history. Toussaint was someone that everybody thought they knew, and someone everybody had a personal stake in. Because of that, it never seemed like the crowd that filled The Orpheum was there to star-gaze or to see the out-of-town celebrities who might be on the show. Costello, Scaggs and Jimmy Buffett brought some theater-filling star power, but The Orpheum was full of people who felt they had genuine relationships with Toussaint and saw him as bigger than any of talent on the stage Friday. I imagine everyone on the stage would have agreed.

Updated November 24, 9:17 a.m.

The comments on "What Do You Want the Girl to Do?" were tweaked for greater precision.