How the Music of Millions Escaped America's Notice, Pt. 1

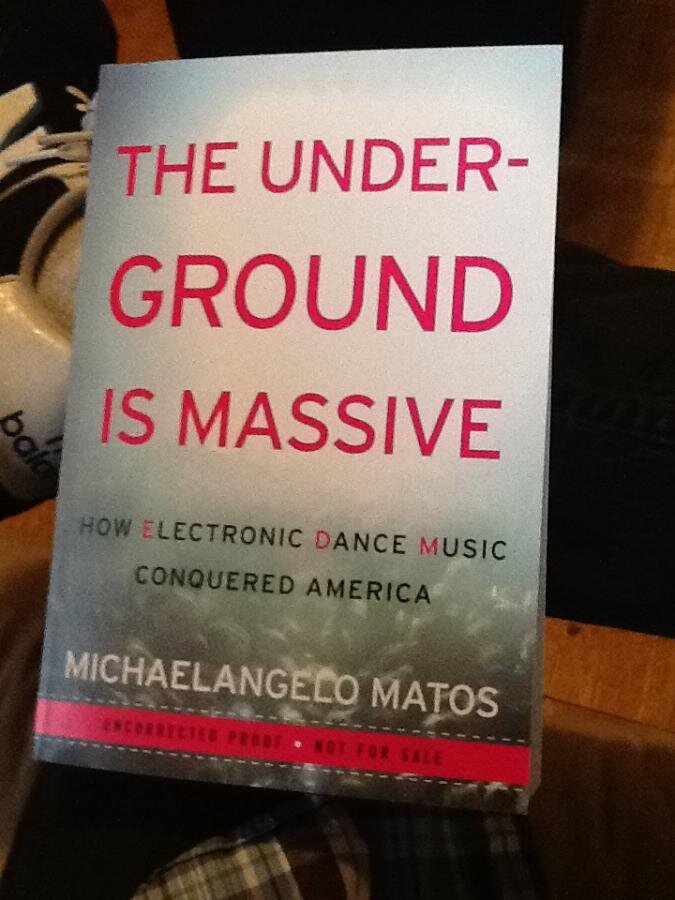

In "The Underground is Massive," Michaelangelo Matos tells the story of how EDM became the most popular and vexing sound in America.

<[Updated] Michaelangelo Matos is understandably a little defensive. He has spent the last year and a half writing The Underground is Massive: How Electronic Dance Music Conquered America, but the music he wrote about has made his work dismissible in some circles. When he appeared on the “On Point” radio program (broadcast on WWNO in New Orleans), one listener called in to say he didn’t consider EDM music, and the condescending sneer in his voice revealed what he thought of Matos’ efforts and book.

Matos has similarly encountered journalists interviewing him about the book who asked him if EDM will last, as if it is a fad.

“It’s amazing that this is still a question. This [music] is not going anywhere. It has not gone anywhere for an entire generation,” he says, incredulous and slightly irked. “In a lot of cases, the question boils down to This is a joke, right? Well no, this isn’t a joke. A lot of people realize it isn’t song-based music, so they think it isn’t music.”

The responses he has encountered aren’t surprising. EDM tests those who consider themselves musically open-minded and knowledgable, and it often shows that they’re not as much of either as they think. Techno and house pioneers from the early 1980s including Juan Atkins, Derrick May, Kevin Saunderson and Frankie Knuckles are best known as names if they’re known at all. Since much of their music was independently released in small runs (compared to major label releases) with minimal distribution, their legends far outstrip awareness of the music that made their reputations.

With the exception of a brief period in the late-1990s when Moby, The Chemical Brothers and The Prodigy were the commercial cutting edge of EDM, it has had a subcultural profile, even though millions of young Americans were going to parties, raves and festivals. Gen X’ers largely missed the story, and Baby Boomers who felt righteous singing “something is happening here / but you don’t know what it is / do you, Mr. Jones?” with Bob Dylan recoil under at the sting of bitter irony.

“This is a real rupture,” Matos says. “One generation’s choice of music absolutely befuddles the other generations. They literally don’t get it and they don’t get that it has been brewing for quite some time.” Now, not only is it the music that reveals most clearly where the music business is at, but it’s the music people need to make money. Most rock festivals have, like the Voodoo Music Experience, included an EDM stage because that’s the music that the prime festival-age audience is listening to.

Matos became interested in EDM as a partygoer first, critic second. He attended his first party in 1993 in Minneapolis, where he lived at the time. Even then, he knew it wasn’t quite what he had read about and was looking for. He knew much of the music and was looking for a more obscure, immersive experience. “It was fun and it was cool, but I knew that there had to be something more,” he says.

It wasn’t until his third party that Matos found what he was looking for—a warehouse with pin spots, lasers, projections on the wall, and music that came from a world outside the mainstream. He didn’t know any of it.

“It helped that I had been reading about this, and I think it helped for a lot of people. A lot of people who wanted to go to raves in cities that were just starting to get scenes were people who’d been reading about raves for years in British magazines and American magazines that were starting to cover it. You had this idea in your mind’s eye based on the photos you’d seen in Melody Maker or NME of what a real rave was.”

Matos almost missed the story as well, though not as badly as his intentional and accidental detractors. He covered EDM for the online electronic music magazine Resident Advisor but was less interested in emerging stars such as Bassnectar and Tiësto than the funkier, more underground artists that interested him. He attended a Red Bull Academy electronic dance music industry get-together in February 2011, where Seattle’s Decibel Festival founder Sean Horton declared that EDM was about to blow up in America. Matos was skeptical because people had made that prediction for years and been wrong for years. Still, he pitched stories to publications based on that premise and was shot down again and again.

“Nobody wanted to hear it because nobody believed it,” he says. “Then Electric Daisy Carnival outdrew Coachella, and people were shocked in America.”

Matos decided that the story needed to be told, partly because so little had been written on the subject. Simon Reynolds’ Generation Ecstasy: Into the World of Techno and Rave Culture was the first major book on the subject in 1998, and a couple of others were written to capitalize on flurries of attention. Matos planned to end his history before he got to festivals and the recent dubstep-driven explosion of attention, but he couldn’t.

“As I kept going, it became obvious that I had to bring the story up to the present day because it wasn’t just a blip.”

In The Underground is Massive, Matos explains how EDM flew under radar in America for as long as it did. He puts flesh on the bones of the basics—techno as a riff on Kraftwerk in Detroit, house as the next step in disco in Chicago—but EDM’s journey is unlike most pop/rock paths because it wasn’t about celebrity, stardom, names or brands. Artists recorded music largely for play in clubs, pressing and releasing limited numbers of white label 12-inch records under a number of assumed names. DJs were stars because of their mixes, not their performances. In his book, and it was a traumatic moment in the dance music community when, in 1996, DJs became big enough as celebrities that attendees watched the DJ insted of dancing. Moby was one of EDM’s mega-stars, but purists turned on him because “he tried to put on a show,” Matos says.

The music spread across the country not through a network of clubs or a tour circuit, but from fan to fan. Someone who went to a great party in another city went home to throw a similar one in his town. It was often unprofessional, frequently inadvertently dangerous, and driven by a passion for cool experiences more than a future in the music business. The conversations about techno, house and raves took place in the relative privacy of regional online message boards in the pre-social media days of the Internet.

Record labels, major labels and to a great degree radio took a pass on techno and house music in the States, so much so that much of the attention they first received came via the British press when England fell in love with electronic dance music and raves became an international fascination. The disproportionate media response to techno in the UK as opposed to America led many to think it was a British phenomenon. But even then, there was little about EDM that conformed to the traditional ways popular music moves through our culture.

“That’s what confounds people. It blew up on its own, in its own fashion and by its own rules,” Matos says.

Next week: Part two of my conversation with Michelangelo Matos on the history of EDM and The Underground is Massive.

Updated June 18, 9:02 a.m.

A reader pointed out that the phrase "small runs" to describe the number of copies of a 12-inch pressed by techno and house artists could be misleading, and that at the high end, Juan Atkins sold 40,000 copies of a record largely out of the trunk of his car. That kind of success isn't the norm in this history, but I've clarified the phrase in the text to indicate that I was thinking of small press runs relative to major label releases.