In the Cult of Cult Bands

The recent biography of a Canadian pre-punk band gives those into bands with specific aesthetics something to think about.

In 2014’s Copendium, The Teardrop Explodes’ Julian Cope praises those who’ve made the most extreme music of the last 40 years. Some are well-known—Black Sabbath, Van Halen, Miles Davis, for example—while others are remain footnotes in the rock ’n’ roll story. Chrome, The Electric Eels, The Boredoms, and many others recorded albums that explored the outer limits of their talents and audiences’ patience, often with the sort of repetitive joy you imagine Keith Richards experiencing when he hit on the “Satisfaction” riff.

Copendium inadvertently serves as an encyclopedia of cult bands, and such acts are easy to fetishize. They’re not just authentic; they’re über-authentic. They make the music they make because they couldn’t imagine doing anything else, and their visions are so personal that no one else could imagine doing it either. Those very specific aesthetics almost by definition translate to audiences that in some cases number in the thousands, and because of that, their albums were rarely mass market products. Instead, many snuck into the world through indie channels, and the people who are into them are almost pathological in their drive to find the music and spread the word, as if people would bail on Taylor Swift if they only heard Amon Düül II.

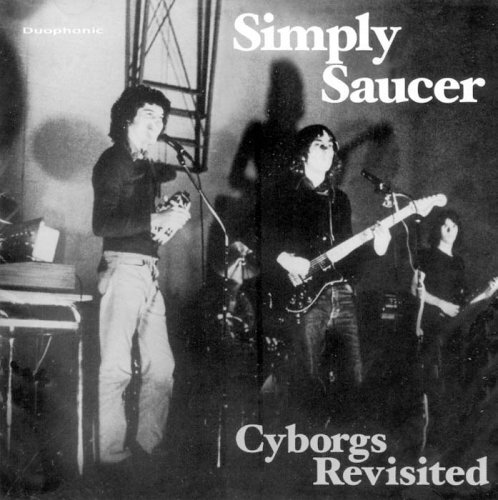

Canada’s Simply Saucer make Cope’s cut, and he glowingly reviews their Cyborgs Revisited, dropping a Bingo card’s worth of references as he triangulates the band’s sound:

by mixing his Lou Reed-fixation with lashings of Barrett-Floyd and early Roxy Music B-sides, Edgar Breau cooked up an artrock as cooly-uncool and as bifocalled as Jonathan Richman's first Modern Lovers LP or even the beguilingly amphetamine and over-arranged provincial garage-prog of the Soft Boys' A Can of Bees.

Later in his review, Cope wrote, “‘Mole Machine’ is an instrumental like ‘Matilda Mother’ given the Here Come the Warm Jets treatment. Ventures/Davie Allen & the Arrows theme guitars emit from a Mike Curb soundtrack and more clatterstompf drumming which combine to give out a Joe Meekian take on space rock.”

Recently, Jesse Locke told the Simply Saucer story in Heavy Metalloid Music: The Story of Simply Saucer, and while it’s valuable for those who discovered Cyborgs Revisited for themselves, it also suggests some caveats for those in the cult of the cult band.

The story largely takes place in Hamilton, Ontario, the Canadian end of the Rust Belt. In the ‘70s when the band formed, the good jobs in Hamilton were in the steel mills, and because the city was within an hour of the larger, more culturally progressive Toronto, Hamilton had a self-consciously working class chip on its shoulder. When punk happened in the late ‘70s, Hamilton’s punk bands took their cues from American influences The Velvet Underground, The New York Dolls, The Stooges and The Ramones, while Toronto’s bands came British-flavored. That same sensibility meant Hamilton could be a hard place for those outside the mainstream.

Edgar Breau of Simply Saucer was one of those people, and he dedicated himself to the pursuit of psychedelic rock inspired by Pink Floyd’s Syd Barrett, but with a pre-industrial garage quality paired with sci fi lyrics. Breau introduced “Illegal Bodies” by saying, “"Here's some Heavy Metalloid music. Unless you have a metal body, they're not going to allow you to walk the streets.”

Not surprisingly, the clubs in a steel town didn’t bite, so Simply Saucer practiced a lot and played a little. It eventually recorded its best six songs in 1974 with Bob Lanois—Daniel’s brother—at the basement studio the two opened, decades before Daniel connected with Eno, U2, Bob Dylan, etc. Locke interviewed Bob Lanois for Heavy Metalloid Music, and while Dan didn’t get the band at all, Simply Saucer excited Bob despite its rawness.

“Basically, they could barely play,” laughs Lanois. “That’s the main thing I can remember. They could barely get to the studio on time, barely get their instruments in tune, and barely play their own songs. I knew how to deal with people even at my tender age, and I whipped them into shape. The main thing I was dealing with was that they weren’t taking the session seriously. But because of the kind of person I guess I might have been back then, I was able to work through that. I thought, ‘Hey man, these kids got something. I’m going to whip their asses.’”

Those recordings became Cyborgs Revisited when it was released in 1989, almost 20 years after the band had called it a day. The irony Cope and other Saucer cultists missed was that the tracks were intended as demos, and not something the band or Lanois considered a finished product. “Bullet Proof Nothing” features a moment when Breau’s guitar drops out—an erased flub that the band ran out of money before it could fix. When you hear Cyborgs Revisited, you don’t hear Simply Saucer as it or Lanois would represent it; you hear a recording that does just enough to give the club bookers (that ignored them anyway) a reason to hire the band. The tracks are provisional, but they’ve become definitive through the accident of their release. Once you know that, you wonder how many other cult heroes are represented by music that doesn’t sound the way they intended.

Locke underscores this irony when he writes about Breau’s reaction to Hamilton writer/record store owner Bruce Mowat belatedly releasing Cyborgs Revisited. The lineup that recorded the album didn’t last much longer, and each subsequent lineup curved the band closer to “normal.” Simply Saucer had enough in common with punk bands to find some success in Toronto but not enough. Before the release of Cyborgs Revisited, Simply Saucer’s musical calling card was the 1978 single “She’s a Dog,” which on its own would give you no reason to think a psychedelic pre-punk album might lurk in the band’s back pages.

Because Cyborgs Revisited was so unlike what the band became, Breau was ambivalent about its release and the acclaim it found. On one hand, it was exciting, particularly since his main musical gig at the time was playing solo acoustic guitar for a few hours once a week at a club. But nobody wants to discover that you made your best music three lineups ago, particularly when you invested your time, energy, creativity and hope in each theoretical upgrade:

“It was a strange experience for me when the album came out,” says Breau. “I was so far removed at that point. The vinyl made a big impact and there were lots of great reviews, but when Bruce’s copies eventually went out of print it became hard to find. He used to call me to ask about getting another edition released, and sometimes I wouldn’t even answer the phone. I was really weirded out by the record. It brought the past back when I wasn’t prepared to face it.”

Locke’s writing marks him as part of the band’s cult. Only the true believers write sentences like “The six songs that would end up filling out side one of Cyborgs Revisited are some of the most unhinged post-Velvets/ pre-Voidoids proto-punk expressions ever laid to tape. These recordings, initially intended as a demo, burst from the seams with blitzkrieg guitars, submachine snare drums, and the electronic dreams of Simply Saucer’s own metal machine maniac.” So much hyperbole. There are a number of possible books to be written that use Simply Saucer as an example of a local band in context—in relation to its city, its era, the scene it partly inspired even after it stopped playing—but Locke simply assumes Simply Saucer’s greatness and tells the story of its formation, dissolution, and post-Cyborgs afterlife without questioning or evaluating any step along the way.

In a way, his decision makes sense. Who would read the book but those who know Saucer or discovered them through Cyborgs Revisited? He sideswipes some of the other possible narratives and spends a lot of time making an unconvincing argument for Simply Saucer’s influence over Hamilton psychedelic bands, but his primary impulse is to simply tell the band’s story. All moments and incarnations are treated as equal with no consideration for what changes in the band and its audience might mean. It’s fair to think about what a reunion show means when it is driven in large part by the belated discovery of a 20-year-old album. Is the band covering itself? Is the audience there to see a zombie rise? These questions don’t get asked.

Locke is hardly alone here. It’s pretty common for members of the cult of the cult band to start from the premise that the band is great and go from there. Kevin McAlester’s 2005 documentary You’re Gonna Miss Me on garage rock hero Roky Erickson lingers over every domestic act Roky performs, no matter how dull. When you’re in the cult, it’s interesting if the acid-damaged Roky does it. I recognize this phenomenon because I’ve been a part of the cult myself. One of the longest pieces I wrote while at OffBeat was a profile of the enigmatic Bobby Lounge, whose manager referred to him as the best piano player who can play in only one key. I no longer think the piece holds up for its length, but at the time I felt that as the first person to account for Lounge’s decade out of the public eye, every detail mattered. I was going to be the starting place for those who would discover him in the future, so I wanted it to be a good starting place. Subsequent investigations into Bobby Lounge have yet to take place, so I may have been caught up in the excitement of being the guy who helped the world discover the eccentric genius of “Take Me Back to Abita Springs” and “Muddy River” and erred on the side of too much.

I’m also a fan of Cyborgs Revisited, and when I wrote a piece on Athens, Georgia’s Dark Meat for the L.A. Weekly, the band’s leader and I bonded over Simply Saucer. When I got the album, I put “Nazi Apocalypse” on mix CDs for a number of friends because in my mind, they needed to hear it. In Copendium, Julian Cope writes as a fan too, albeit one with extreme tastes. He stays in his lane though, and when he veers into the band’s story, he does so only to help readers hear what he hears.

If we’re going to actually tell the stories of cult artists, sharing the love is not enough.We face choices too. We can feed the myth that the artist would have been bigger if not for the failings of the industry, the marketplace, and the sheep who buy bad music, or we can try to understand why something so remarkable didn’t land. Or how it happened at all. In Heavy Metalloid Music, Simply Saucer sounds like a band that should have had a following that filled arenas instead of bars, even though the details of Saucer’s life and the recorded evidence make that narrative hard to buy. The failings weren’t all a product of an uncaring public, bad luck and financial woes, and stories that examine the artists’ complicated relationships to success, art, talent, and perhaps the world around them are better than conventional narratives. If nothing else, artists with very specific, unconventional talents deserve accounts that are as firmly rooted in the truth as they are in their personal aesthetics. Rock ’n’ roll myths are fun, but the reality is usually stranger and more compelling.

var myNativeAd = { consumerKey: "hbfXS0hRQY4yB2IIyHFh29",use_external_settings: true }