Jazz Fest: The Complicated Afterlife of Fats Domino

Prematurely declared dead on the side of his house, Fats Domino lived 12 more years. Or did he?

The Tribute to Fats Domino on Saturday at The New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival presented by Shell is the natural end to the last chapter of his story. He was first and famously proclaimed dead during Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and lived 12 years after that, so why not another six post-mortem months?

The Jazz Fest tribute takes place Saturday at 1:45 p.m. on the Acura Stage with a predominantly New Orleanian talent lineup that will include Bonnie Raitt, Jon Batiste, Irma Thomas, Deacon John, Davell Crawford, Al “Lil Fats” Jackson and the Fats Domino Orchestra, That lineup is unlikely to reconsider Domino’s songs the way some artists did on Goin’ Home: A Musical Tribute to Fats Domino. For that 2007 album, the Tipitina’s Foundation, Adam Shipley and Bill Taylor corralled Raitt and Thomas as well as Neil Young, Paul McCartney, Lucinda Williams, Lenny Kravitz, Robert Plant, and many more to record his songs, but a lineup like that one would close the Acura Stage instead of Rod Stewart or Aretha Franklin, who was originally scheduled in the final slot Saturday.

Should the festival have gone for something like that? Good question. An all-star Domino tribute would have been far more of an event than Rod or Aretha in a lineup the could use a little appointment listening, but it would have been expensive and logistically hellish. And, at a time when New Orleans artists rarely close the main stages or get the long time slots, letting New Orleans’ talent salute one of their own seems like the right move.

A Jazz Fest tribute to Domino is a natural, particularly since his appearance during the 2006 festival revealed what the last chapter of his story would look like. Domino was scheduled to close the Acura Stage that day but didn’t, instead pulling out and claiming illness. He walked onstage and tipped his hat to the crowd before exiting the stage and the Fair Grounds, leaving everybody a little confused because he didn’t look or act sick.

That became the Domino M.O. He seemed outwardly fine, but he was never fine enough to perform or do more than make an appearance and wave. His 2006 album Alive and Kickin’ didn’t make a powerful case that he was either as it largely repurposed previously unreleased tracks, but at the same time stories circulated of fans and curiosity seekers who drove by his house, found him there, and stopped to chat in the afternoon over Heinekens.

I dealt indirectly with Domino in the fall of 2006 when I served as editor at OffBeat. We wanted to pay tribute to him in the January 2007 issue and at the 2007 Best of the Beat, and his friends and family wanted it to happen too. The only challenge was Domino himself. We were assured that if he knew people expected something from him, he would make excuses at the last minute and no-show. To get our cover photo, we arranged for photographer Greg Miles to be ready to shoot him at his Caffin Avenue house, and friends planned to take Domino there. He had some memory issues, and if he was told that he had agreed to the photo session once he arrived, he’d assume he had and go through with it.

When friends picked him up from his daughter Adonica’s house on the Westbank, I got an urgent text. He didn’t want to go to Caffin; he wanted to go to Tipitina’s. I let Miles know and he and his assistant hurried Uptown to set up his backdrop, lights and cameras in Tipitina’s before Domino arrived. When I arrived, Bill Taylor and Tipitina’s owner Roland von Kurnatowski introduced me to Domino, who had a briefcase that he kept close to him. What did it hold? Money? A gun? We never found out, but when Miles briefly started to push it out of the way with his foot to move it out of a shot, Domino quickly shot him a look that let him know his foot and the briefcase were never to touch again.

As predicted, Domino groused that he didn’t remember agreeing to any photo shoot, but he went along with it anyway. He had a good sense of humor and joked, but he also had a faint fuzziness that seemed to hang over him until the lights were on with a camera pointed at him. Then the fog cleared and the charisma that helped father rock ’n’ roll in the 1950s was as present as ever. He knew how to create his image, even when everything else about being Fats took more work than it used to.

We made it clear to his family that at the House of Blues, he could play if he wanted to. We seated him in the balcony near a door that led to the stage just in case, but nothing came of it. The closest he got came when he arrived at the stage door and entered the backstage with his family and friends, posing for pictures with the famous, infamous, and people like me. He had graciousness down like muscle memory, and when those who bought the Domino biography Blue Monday from from author Rick Coleman’s merch table took it straight to Domino for an autograph during the show, he handled them with a smile.

In 2007, Taylor and von Kurnatowski took Domino to New York City to perform on NBC’s Today Show to draw attention to Goin’ Home, but it was never clear that he would actually play until he did. The night before the performance, he quit a version of “Blueberry Hill”—the song he was to play on Today—after a verse and a chorus at a tribute concert. Later in the show though, he happily backed up Lloyd Price on piano for “Lawdy Miss Clawdy,” just as he did when Price recorded the song at J&M Studios. In May that year, Domino played one final concert at Tipitina’s that remained a Maybe even after it started. He performed for 10 minutes then started to leave the stage, only to be intercepted by WWL’s Eric Paulsen, a friend of Domino’s who accompanied him to Jazz Fest in 2006. At Tipitina’s, he suggested Domino go back and play “Blue Monday,” which led to another 20 minutes of a show before Domino left the stage for the last time. Before the show, he didn’t seem to know he was expected to perform. “This is a surprise to me,” he said backstage.

Those in New Orleans knew that getting Domino to do anything was a challenge; some out of town assumed he was simply an underutilized resource. He was 81 in 2009 when an Austin-based promoter built a benefit concert, “The Domino Effect,” around a Fats performance. Tickets moved skeptically for the show at the Smoothie King Center, then stalled when Domino announced that he wouldn’t be able to play. With that centerpiece scrubbed, the tribute to Domino that the promoter promised fell apart as well, leaving a testy Chuck Berry, a preening Little Richard, Junior Brown, Keb’ Mo’, Taj Mahal, Wyclef Jean and Ozomatli to pick up the pieces and play to 2,000 or so people in a building that holds 17,500.

“The Domino Effect” mirrored the dynamic between New Orleans and the rest of the country at the time. People around the world and certainly across America looked at New Orleans and saw a beloved entity that could work if it only had their know-how and moral compass. They ignored or didn’t realize the conditions on the ground. Donald Trump announced plans for Trump Tower New Orleans two days before Hurricane Katrina and continued to believe that he could build the city’s tallest building as late as 2010, when the realities of the market and the city defeated him. Recovery Czar Ed Blakely came to New Orleans with visions of cranes in the sky, but by 2009 he was out of the recovery business and dismissing the city as too racist and lazy to rebuild properly. “New Orleanians expected someone else to do it all along," he said in an interview that year. "They never expected to do it themselves."

In the years after Jazz Fest, it was never clear what Domino’s issue was. Was it simply stage fright? When he was out of the limelight or when he got rolling, he could have fun and play well. But he rarely did. Was he feeling his age? He was 77 and a widower when Hurricane Katrina hit. Was he drinking too much? Writer Keith Spera noted Domino cracking his first Heineken of the day at 9:30 a.m. before flying to New York in 2007. Was he slyly playful? Was he ill? No single explanation seemed wholly satisfactory, but his health issues were plain to see in 2010 when Eric Paulsen brought Domino’s long-time bandleader and producer Dave Bartholomew to see him at his daughter’s house. The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame planned to honor the two that fall, but Domino announced that he wouldn’t be able to make it. Bartholomew came by to reminisce with Domino for WWL-TV’s cameras, but he had to carry the conversation as Domino often seemed vacant.

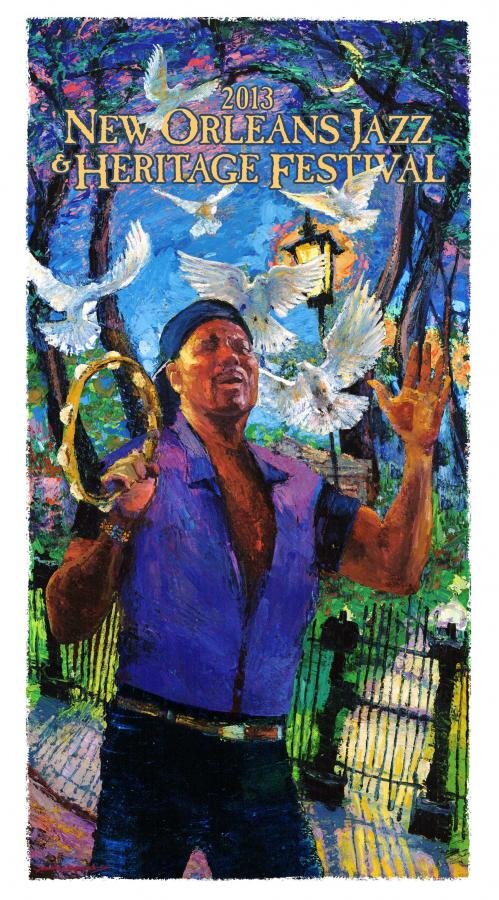

Fats Domino was New Orleans’ biggest music star along with Louis Armstrong, but he toured for the last time nine years before Katrina, then settled into legendhood with all the vagueness that implies. He lost context, and nothing illustrates that like his Jazz Fest posters. Richard Thomas presented Domino in 1989 in a series of Warhol-esque silk-screened images, putting Fats on a level with Jagger and Jackie O, focusing on the magnitude of his stardom.

Domino’s image became less specific when James Michalopoulos painted him on the 2006 Jazz Fest poster. Michalopoulos’ poster abstracted Domino out of any reality as it situated a 1950s version of him at a piano in the middle of a French Quarter street. Logic, gravity and balance are out the window, leaving Fats to float literally and figuratively in a mythical, equally unmoored New Orleans. Michalopoulos’ image promises a magical good time in a magical place, but by borrowing a familiar image of Domino, the poster presents a commonplace magic.

Domino returns on this year’s poster in an image that looks like Terrance Osborne riffed on Michalopoulos’ poster. Once again, Domino is playing piano in the street, but a grand piano instead of an upright. He’s in the Marigny or Bywater or Treme, but the location is lit by strings of light overhead unlike anywhere in New Orleans. The perspective that Michalopoulos bowed, Osborne warps to produce curved roads that none of our grid-like neighborhoods have. The wood planks on which Domino’s bench and piano rest suggest that he’s performing on a porch looking down an alley, but it would be a hell of a porch if a grand piano fits on it.

There’s no reality in the image, just as there’s none in those before it. Still, Osborne’s poster takes Domino and New Orleans one step past Michalopoulos’ poster into realms of abstraction. Allan Toussaint played an equally illogical piano in an equally unreal French Quarter in 2009, and Dr. John, Louis Armstrong, Jimmy Buffett and Trombone Shorty have all played in trippy, generic French Quarter locales. The idiosyncrasies that made Domino and New Orleans distinctive are leveled in these posters as he and the city are reduced to icons that can be summed up in a characteristic or two. In 2018, Domino is a smile and a ring, and New Orleans is a magical city that might be on fire if the bright yellow-orange in the background is to be believed.

Unfortunately, I fear the Domino described at the tribute will be the one in the poster—the one that offers no drag or resistance to any narrative that tries to fold him in. The one who lived 12 complicated years after Hurricane Katrina and dramatized late life issues including a desire to go through his last years his way, regardless of his fame, was far more compelling.