"London Town" Illuminates the Impact of The Clash

The coming-of-age movie presents Joe Strummer as the magic punk.

The movie London Town started impulsively. “When my agent said, What’s your dream project? I’d love to find a story about a kid discovering The Clash,” director Derrick Borte recalls. “I hadn’t really thought about it. The words just came out.”

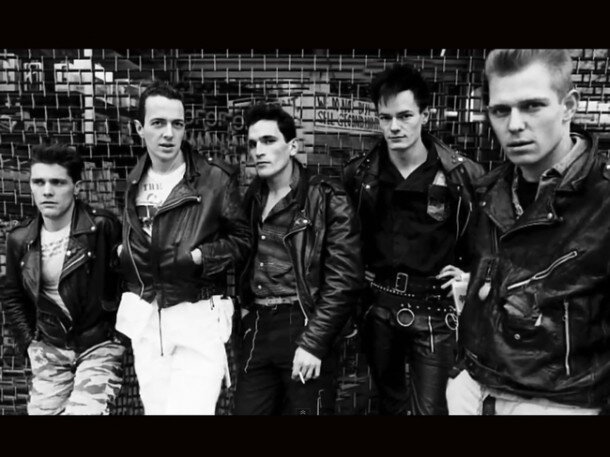

London Town will play in New Orleans at Zeitgeist Multi-Disciplinary Arts Center Friday and is on Video on Demand now. It depicts a London in 1978 when England was in transition. Shay (Daniel Huttlestone) starts the film as the 15 year-old son of a retired musician who at some point hung up his rock ’n’ roll dreams to run a piano shop. Shay’s mom (Natascha McElhone) is in London pursuing her own musical dreams—one of the features of the story that rings true to punk’s anyone-can-do-it aesthetic—sends Shay a cassette of punk songs focusing on The Clash that sets him on his path.

Borte knew that he didn’t want to do a bio pic. “I felt like the band’s music and its effect on other people was more important to me than any personal stories of the band,” he says. Only Joe Strummer (played by Jonathan Rhys Meyers) gets any meaningful lines in the movie, and the other band members are only Mick Jones, Topper Headon and Paul Simonon to the extent that the actors playing their instruments bear a passing resemblance to them, particularly with the help of wardrobe. That has caused some Clash purists who want to see the film as The Clash story to be critical, but Borte is very clear about the movie he made and its motivation.

“It’s the story of a kid—much like I was—whose life was changed by listening to The Clash,” Borte says. “Which really happened to me.”

In Borte’s case, he was in America, and it was friends in high school who gave him a cassette with The Clash. For him, London Town is a coming of age story, and Strummer and The Clash are the vehicles that help him take the first step out of childhood toward adulthood. According to Borte, less dedicated fans have got more out of London Town. Teenagers who’ve seen it have found the movie to be a way into British punk, The Clash, and music they’ve largely only heard about without preaching. “It puts The Clash in a context for them,” he says.

In a sense, he’s right. London Town effectively recreates the world around punk in London in ’78, where pockets of people talked progressive politics and drank all night, and where record vendors in open-air markets were as significant as any record shop. Violence was always possible, and the punk “us vs. them” attitude was real because the punk “us” only genuinely constituted a few hundred people at first against a city that sometimes felt free to physically attack them.

But the tricky tonal line that London Town walks and that challenges some viewers is that Shay’s story and particularly his relationship to Strummer borders on urban fairy tale, with Strummer as a leather-jacketed Gandalf blowing improbably into Shay’s life, and when we last see him in the movie, there’s no sense that he’ll stay a part of Shay’s life two days after the closing credits roll. That’s not exactly how Borte sees the film, but he gets it.

“There’s two sides to this topic to me,” he says. “There’s an element of magical realism to it. If Shay were telling his story today, this is the way he would tell it, but who knows what the reality of the situation was. At the same time, I heard over and over again from people as I was making the film that in London in 1979, Joe was my next door neighbor, or Joe lived next door to my grandmother. Back then, you could have these random encounters in a way that’s quite a bit different than today. There’s a possibility that in London at that time, you could have had a brush with one of your idols that was real.”

Relationships in the movie point to this notion of Strummer as an almost magical figure. As Borte points out, Shay’s father is a rock who quit and is tough on Shay as he tries to be a single father in tough financial and emotional times. In contrast, “Joe is the coolest guy in the world,” Borte says. “That makes Joe almost a fictitious character. I’m sure there’s a classic Greek story in there somewhere.”

Strummer in particular is an appropriate figure to hand such a story on. The son of a diplomat, John Mellor chose to adopt the role of a working class hero, and “Joe Strummer” became a communal creation made in part by him and in part by fans who hung their own hopes and meanings on him. In all likelihood, he’d have had to move monthly to have lived next door to all the people who claimed to have been his neighbor.

“I almost feel like punk was smaller than The Clash,” Borte says.

Not surprisingly, the music was crucial to Borte, who explored a number of ways or representing the sound at the heart of the movie, and particularly that of The Clash. He considered licensing tracks, but in the end decided to walk the music stores in Soho music stores to recruit his own band to play the songs with the movie’s Strummer, Jonathan Rhys Meyers. “I found Dave Page, the guitar player, and then Dave, Johnny and I held auditions for the other parts,” Borte says. The decision works because more than sounding like The Clash, they sounded like a Clash still in the process of finding itself. The decision also avoided the potential disjunction that comes with seeing band members who look a little like The Clash sounding exactly like them.

Working with the band turned out to be some of the most fun he’d ever had on a production, Borte says. “Something that started off as the thing I felt the most pressure about turned out to be some of the most gratifying experiences of the whole production.”

In a crucial scene, Shay’s mother reveals the progress of her musical dreams when she performs an acoustic, cabaret version of The Only Ones’ “Another Girl Another Planet.” Picking the song for her to sing was a challenge. What worked for the character? Borte considered a Blondie song even though Blondie was a New York band, and eventually settled on “Another Girl Another Planet” because while some people would know it, it wasn’t so big that viewers would automatically know it as a cover, particularly when rearranged for acoustic guitar and voice. “It wouldn’t take people out of the movie,” he says.

When she plays, we can see that she’s yet another charming, capable singer, but not more, and you know in one scene that her musical story won’t end any better than dad’s. “We had to have her perform as part of Shay’s reacquaintance with her and part of explaining her story,” Borte says. “Otherwise, What if she’s going to be a huge rock star? You don’t know unless you see something.”

The Clash first appeared on the silver screen in the 1980 movie, Rude Boy, which was also as much about the band’s impact as the band itself. Strummer, Jones, Headon and Simonon play themselves in the movie, which is ostensibly about the adventures of their would-be roadie Ray, played by Ray Gange. Borte got in touch with Gange and used Rude Boy’s footage of The Clash at Victoria Park for the Rock Against Racism performance—musically dubbed with music by London Town’s band. Borte also gave him a small part as a Clash roadie as a nod to his film. Talking to Gange on the set reassured Borte he was on the right track.

“I was there, and you’ve captured the essence of what it was like to spend time around these guys in 1979,” Borte remembers Gange saying. “That meant a lot to me because I felt a lot of pressure as a Clash fan to get it right. To get the sound and vibe right.”