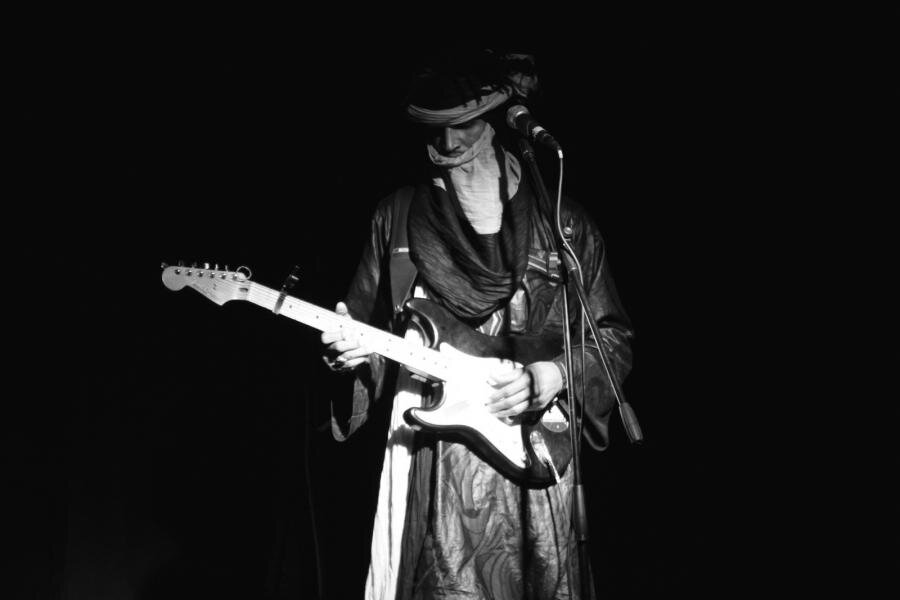

Mdou Moctar Takes Desert Blues Electric at Jazz Fest

Moctar will play the first Sunday of Jazz Fest in the wake of his first full-band release.

In the land of the underdog story, Mdou Moctar is king. Born in the Tuareg commune village of Tchintabaraden, Niger, Moctar was raised in a strict Muslim household in which music was forbidden. He built his first guitar, a lefty five-string, from wood and bicycle brake cables and practiced it in secret, with no formal instruction. Now, he’s touring the U.S. behind his third studio album, Ilana (The Creator). He’ll play Festival International de Louisiane in Lafayette on Friday, April 26 and Saturday, April 27. On Sunday, April 28, he’ll play Jazz Fest, taking the stage in the Blues Tent at 12:30 p.m. and the Cultural Exchange Pavillion at 3:10 p.m. Then, on Monday, April 29, he'll play Santos (1135 Decatur St.).

“I started to play music because I felt something inside me,” he says. “I wanted to be a musician because I see musicians make people happy, and that is what I need in my life.”

Even today, Moctar feels being a musician goes against the principles of Islam, but he’s come to reconcile his passion with his belief system. “Music is my job, and Islam is my religion,” he says. “I don’t insult people. I do not hurt people. In everything, there is evil and there is well. I took the good side. I know what I do in music is something that makes people very happy. With this music, I'm helping poor people who do not have something to solve their life.”

Moctar moved to the city of Agadez as a young adult to look for work. His first gigs were weddings there, where he played customary Tuareg folk music. But his first album, Anar, recorded in 2008 and distributed via bluetooth transfers and cell phone memory card swaps, was far from traditional. While his acoustic guitar playing on the record mostly adheres to the repetitive pentatonic riffs of his Tuareg predecessors, he complements it with drum machines and heavily Auto-tuned vocals much more typical of the Hausa, another Nigerian ethnic group.

“I’m a curious person,” he explains. “Hausa music is popular in Agadez, and I listened to how they use Auto-tune and the drum machines, and I thought, Why not try this with Tuareg music? It was just a curiosity and an experiment.”

Anar garnered global attention in 2011, when its title track was released on the compilation album Music from Saharan Cellphones, via Portland-based label Sahel Sounds. After that album’s release, label founder Chris Kirkley went on a mission to track Moctar down. Through a series of loose connections, he managed to get Moctar’s number. Kirkley asked Moctar to send him some tracks, but with no internet connection, Moctar had to confirm his identity by playing for Kirkley over the phone. Shortly thereafter, Kirkley visited Moctar in Niger and bought him his first electric lefty guitar.

Moctar put out his first live album, Afelan, on Sahel Sounds in 2013, and released Anar in full the following year. In 2015, he collaborated with Kirkley on Akounak Tedalat Taha Tagozai, the first ever feature film in the Tuareg language of Tamasheq. The movie is a Saharan remake of Purple Rain. Its title translates as “Rain the Color of Blue with a Little Red in it" because there is no Tamasheq word for “purple.” Moctar had never heard Prince’s music but connected on a deeper level with the story of Purple Rain’s protagonist, The Kid, who becomes a musician against the wishes of his abusive father. The father in Akounak Tedalat is closer to Moctar’s own. A pious Muslim, he burns his son’s guitar, telling him the instrument is for drug addicts and alcoholics.

In 2017, Moctar released his second studio effort, Sousoume Tamachek, a return to traditional acoustic Tuareg music, which he refers to as “desert blues.” But on his new project, Ilana (The Creator), he takes an entirely different approach. Ilana is Moctar’s first fully electric studio album and his first project with a full band. “If I’m doing a proper album, I like to work with a full group,” he says. “There’s a collaborative effort. It gives me a space to plunge into the music and explore what it can be.”

The album weaves Moctar’s newfound western influences into the assouf guitar style he grew up with. While he’s been told his sound is reminiscent of delta blues, he hasn’t had access to those early Mississippi sounds. Instead, his touchstones come from the classic rock canon. “I like Prince, I like Eddie Van Halen, and I like Jimi Hendrix,” he says. “I like the tapping that Eddie Van Halen does; it’s something I try to use.”

Moctar’s tone on Ilana is triumphant, but thematically, he’s dealing with serious material. He’s highly critical of the French imperialists who continue to exploit Niger for its uranium resources, though the country has been independent since 1958. In a recent interview with The Guardian, he described his people as “modern slaves,” but he gives MSM a slightly more optimistic take. “I would like Americans to understand that the Tuareg people are a free people,” he says. “We are in the desert, [and] we do not have clean water or electricity, but we still have hope. We have a very beautiful culture, and all the people, all the colors, all the religions that come to us are more than welcome in the desert. We have difficulties in education and difficulties with hospitalization. We are a people who respect women very much. We have much pity on children. The whole world must understand that we need our freedom in our country, in our desert.”

Ilana’s title track is a prayer to the creator to guide Moctar’s people through this difficult moment in history, but he also offers concrete advice to young Tuareg listeners. “It’s impossible to be a leader without studying,” he says. “For all the presidents of the world, there isn’t one that didn’t study. To become something today, you must go to school. The most efficient weapon in the world today is the pen.”

Moctar completed his first American tour in January and began his second at the end of March. He’s been positively received across the board. “For me, wherever I play, I’ve had the chance to play in front of my supporters, and I see the same thing: People who are with the music one hundred percent,” he says.

Jazz Fest will mark Moctar’s first performance in New Orleans and his first experience of jazz. “I don’t know ‘jazz,” he admits. “I can’t say that I know any of the classifications for music that you use because I never had a chance to study music. But I love music, and I want to hear it.”