Our Spilt Milk: Andy Shauf's Wintry "Skyline," the League of Extraordinary Gentlemen's "Tempest," and New BadBadNotGood

Our favorite things this week include the cozy "Neon Skyline," Alan Moore's conclusion to a 20-year story, and BadBadNotGood's cross-genre experiments.

The semi-wintry temperatures must be taking effect because all I’ve been wanting to do lately is cocoon myself into a ball of blankets on the couch and sip a warm cup of tea. Thankfully, I’ve found the perfect music to preface a long nap: Canadian singer-songwriter Andy Shauf’s new concept album, The Neon Skyline, which came out last Friday. Shauf is a crafty storyteller. Each song on the album forms a snippet of a larger narrative, telling a story which takes place over one night. The narrator heads to a dive bar and knocks back drinks while reliving a romantic crisis. Describing The Neon Skyline, Shauf has said: “Essentially it’s an album about nothing”. Yet whether Shauf realizes it or not, he’s great at stringing together a story and equally adept at composing intimate, soft folk-rock arrangements. His songs amble through and then pass, like kicking up a cloud of dust and watching its particles float away in the air. (Devorah Levy-Pearlman)

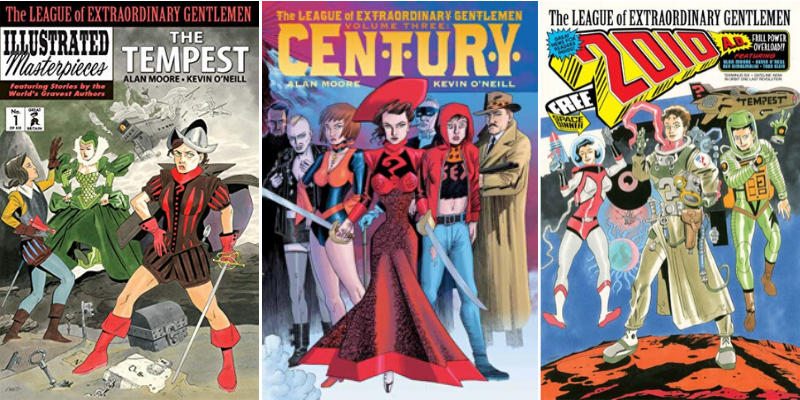

The contrarian in me wants to declare The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen to be comic book writer Alan Moore’s magnum opus, but that would be wrong. Watchmen is clearly more influential and more perfectly executed, but Moore has been working on The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen since 1999. The story sprawls across 20 real-time years, five graphic novels, three graphic novellas and at least 400 story-time years with the premise that all pop culture characters lives in the same universe.

The story recently concluded with the publication of The Tempest, which collected the last six issues of the story. The Tempest is spectacular and the second-worst place to dive into the story. The 2007 installment, The Black Dossier, borders on impenetrable at times, so you need to be attached to the characters to fight through it. The Black Dossier is also the place where the League transitions from good fun into something more radical, so it’s worth the effort. The series began with heroes and heroines from Victorian pulp literature having adventures, and in addition to being good stories, Moore gave readers new ways to think about characters created by H.G. Wells, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, and Robert Louis Stevenson. Those stories are the starting places.

The Black Dossier charges the whole projects with nitrous and broadens the story’s reach as Moore pulls in Shakespearean characters—the pop culture of an earlier time—and maps George Orwell’s 1984 on the post-World War II England. It’s when The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen becomes a grand project with more on its mind than freshening up some of literary history’s most shopworn characters. One of the book’s most electric touches came when Moore gave us a nihilistic James Bond that made perfect sense, and characterizations like that similarly give Century the juice it needs to get through a sometimes bleak story. Century takes place over a hundred years and ropes in The Rolling Stones, Aleister Crowley, Rosemary’s Baby and Mary Poppins. Those who made it through Century were rewarded with a series of fairly straightforward adventures starring Captain Nemo’s daughter as the new captain of the Nautilus, who meets Lovecraftian elder gods, Tom Swift, the robot from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, and Charlie Chaplin.

By the time we get the Nemo trilogy and The Tempest, the extraordinary gentlemen are all women or gender-fluid (in the person of Virginia Woolf’s Orlando), and the comic book’s vocabulary has been shaped by all the narrative vehicles Moore has borrowed from along the way. He and artist Kevin O’Neill shift gears to use pages that mimic different types of comics to help tell the story. When O’Neill depicts The Blazing World, he does so in gorgeous 3-D (3-D glasses are provided). The series suggests that stories and their tellers are not to be trusted, and Moore and O’Neill signal that this warning applies to them as well.

For all of The Tempest’s reach and narrative density, it also delivers simple, effective surprises, like finding The Beatles’ Yellow Submarine beached and falling apart near a Blue Meanie skull with a bullet hole through it. I suspect that if I knew British pop culture better, there would be more moments like that one that feel borderline transgressive. But that isn’t Moore’s game. Throughout much of his comics career, he has taken familiar characters and character types and suggested the possible back stories that lie behind the official stories. In The Tempest, Moore wraps up the threads he introduced in The Black Dossier—threads that made that installment and everything after feel like expressions of Moore. He writes his love of comics and loathing for the industry into his work, most explicitly in brief histories of British comic artists that the business screwed in his estimation, and Moore’s antipathy for institutional power is consistent with his embrace of anarchy—a belief that found expression in his 1980s series, V for Vendetta.

As much as I enjoyed The Tempest, I’m really looking forward to reading the whole story from the beginning. Like life, those first books now seem like part of a different time and a different story, but they pave the way to The Black Dossier. Moore and O’Neill’s panels are as dense and deliberate as Moore and Dave Gibbons’ are in Watchmen, so rereadings not only pay off but are mandatory. The uncertainty that drives Century makes sense for characters who magically outlive their eras as they struggle to find their places in a new one, and in that way the series often feels like a form of meta- literary criticism. The Nemo stories reassure readers that Moore can still tell a straightforward story, which subtly reinforces the idea that the ways he tells his stories matter. I look forward to rereading The Tempest with all of that behind me to see what else emerges from a story that calls storytellers into question. (Alex Rawls)

Some force must be drawing me musically northward lately. I’ve recently circled back to the Toronto-based BadBadNotGood, an instrumental group that I had listened to once or twice and wholly forgot about. The quintet’s Wikipedia genre tags include “post-bop,” “instrumental hip-hop,” “jazz-funk,” “free improvisation,” “electronica,” and “jazz fusion.” In other words, you should be confused what their music sounds like. Their most recent album, IV, was released in 2016 and will surely melt your mind away into a wintry daze. I like BadBadNotGood because they’ve developed an experimental sound that merges the bandmates’ love of jazz and hip-hop in a musically satisfying way. It’s rare to find a record that’s both an inventive musical feat as well as a cozy bedroom listen. IV checks those boxes for me. In December 2019, they released a cover of The Majestics’ “Key To Love” in collaboration with singer Jonah Yano, and I look forward to new releases from the band soon. (Devorah Levy-Pearlman)