"Punk" Does Justice to Punk

John Holmstrom finally presents his groundbreaking fanzine the way it should be seen in "Punk: The Best of Punk Magazine."

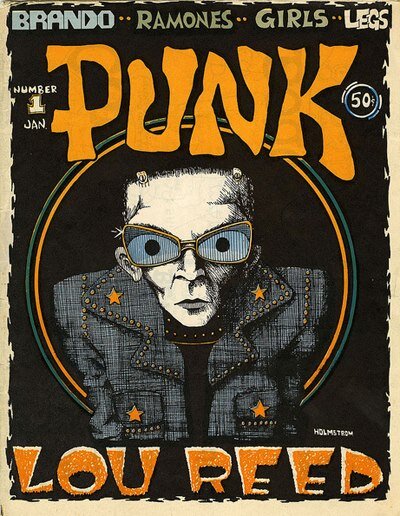

Right from the start, Punk had the sort of branding most magazines would kill for. Its 1975 debut issue featured a lengthy interview with Lou Reed that started during a Ramones show at CBGB and continued into the night. The conversation was one of the definitive depictions in print of Reed as he was often sarcastic, defensive and condescending, but when interviewer John Holmstrom was going for burgers after the show, he wanted to come along. Reed was between the aggressively difficult Metal Machine Music and the confounding-in-its-own-way Coney Island Baby, and the portrait of him that emerged from the Punk interview was of someone more complex and playful than previously imagined.

But the presentation of Reed wasn't the only thing defining about Holmstrom's interview. It laid clear the circumstances of the conversation starting with Holmstrom and Legs McNeil crashing his table while he was at a show, and when they wanted to take a picture, the text includes Reed asking them to wait until he put on his sunglasses. And, with the exception of a couple of photos, portions of it were illustrated and it was lettered by hand. The attitude, the look, and the association with the Bowery punk club were integrally linked to Punk, sometimes to its detriment as punk was largely a coastal phenomenon at the time.

Punk lasted for 17 issues - through the spring of 1979 - and as Punk: The Best of Punk Magazine (Harper Collins) documents, the business was never easy. The magazine combined comics and street-level, nothing's sacred journalism - an unlikely combination - and it started when three friends from Connecticut moved to the Bowery and into an office/living space that came to be known as the Punk Dump, and ended when their last white knight absconded with the back issues as they received threatening letters and were blamed for the failure of the CBGB scene.

Since then, Holmstrom tried to revive Punk twice, once in 2001, but September 11 brought those plans to a halt as the economy's downturn made the idea unlikely, and the singer of one of Holmstrom's favorite band at the time, The Bullies, was a firefighter who died in the World Trade Center. He started Punk againin 2007, but it didn't take. "The problem was always distribution," he says.

After all that, the book has been a labor of love, something that came from a sense of obligation to the the magazine he'd made and the times it documented. "It was so much work that it's more of a relief," Holmstrom says. "It was exciting bringing out the magazine in the '70s." He has spent the past four years scanning pages, tweaking them, and shepherding them through the printing process. Punk: The Best of Punk Magazine presents selections from the magazine because collecting it in its entirety would involve almost 700 pages of magazine material alone. Holmstrom considered reprinting the complete run as a boxed set, but "I don't know if I want to go back and do all that work. I want to do something new."

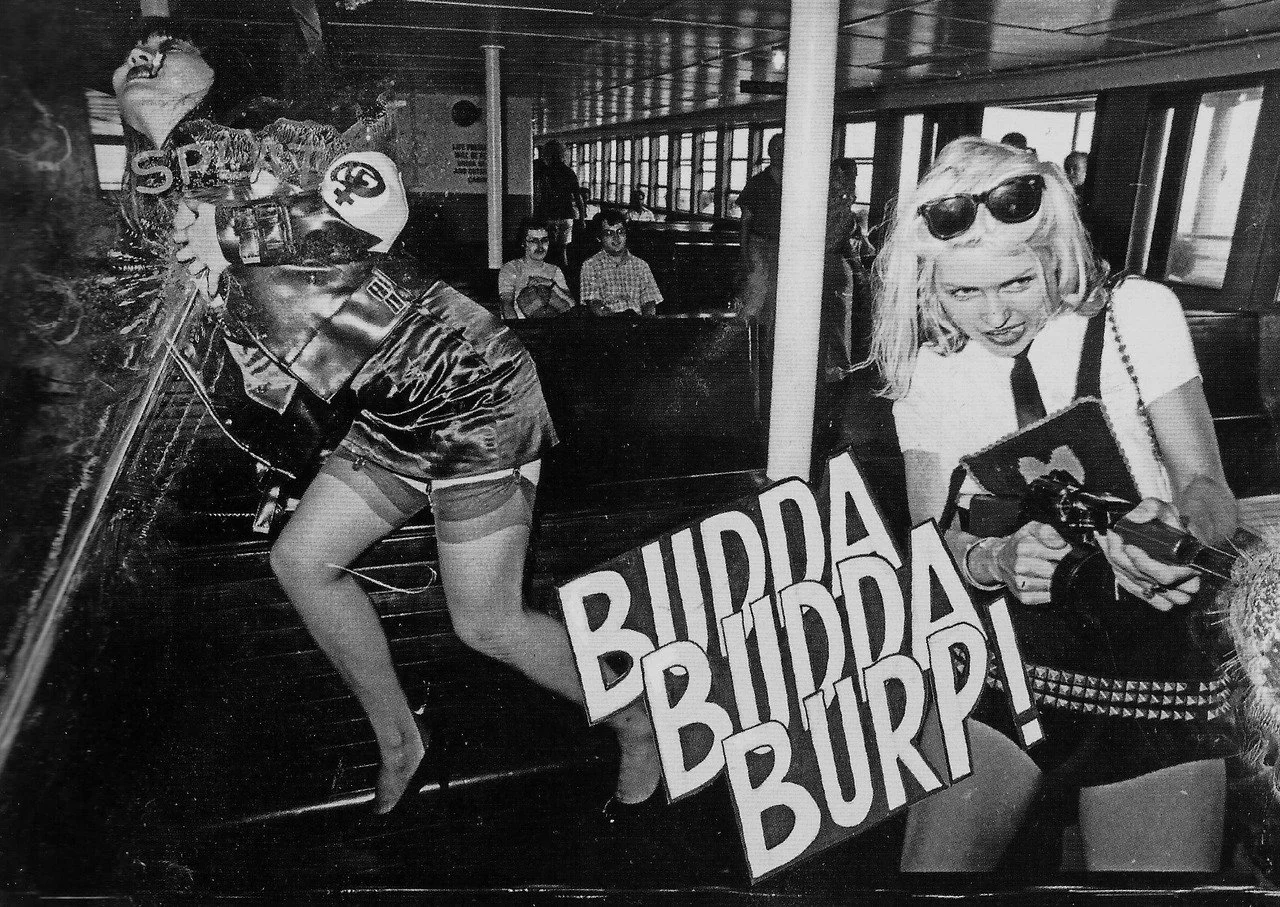

Anya Phillips and Debbie Harry in “The Legend of Nick Detroit” in Punk Magazine

Still, improvements in printing technology have made it possible to present the material the way it was meant to be seen. Two of Punk's signature projects were "The Legend of Nick Detroit" and "Mutant Monster Beach Party," lengthy fumettis telling B-movie stories in photos with members of the New York punk community as the actors. The latter presented Joey Ramone and Debbie Harry as star-crossed lovers, while the former featured Richard Hell as a two-fisted action hero. Printers at the time treated these and many other photos in the magazine roughly, robbing them of detail. Before the new book, you couldn't see that it was raining during the first shots of "Nick Detroit."

"We'd get these great photographs, and they'd come out looking like mud," Holmstrom says. "Sometimes it would be depressing looking at the magazine: Man, how did they screw this up?"

Holmstrom came to Punk with a background in comics. His father was an illustrator and his sisters could draw, so art seemed like a viable direction. At the same time, he was interested in writing, so it was his good luck to take classes at the School of Visual Arts with comics legends Harvey Kurtzman and Will Eisner. Holmstrom had loved comics since he saw them in the newspaper as a child, and Kurtzman and Eisner were both noted for the way they integrated visual and written storytelling. Eisner was working on his project A Contract with God when Holmstrom apprenticed for him, doing business-related functions that served him well when he started Punk.

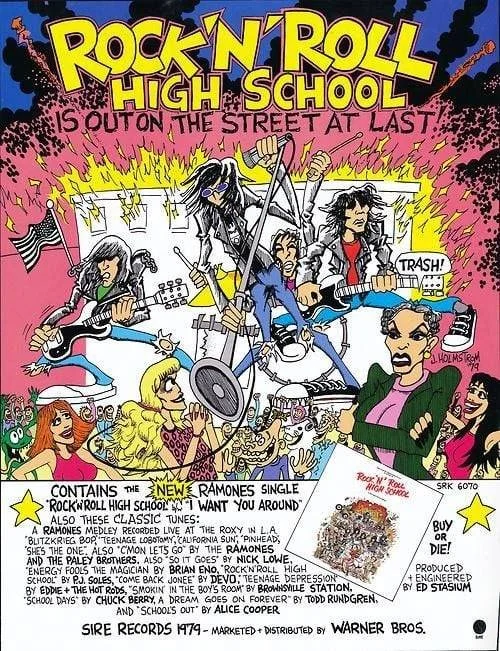

Holmstrom was always interested in rock 'n' roll and comics, and while he was at the School for Visual Arts, he envisioned an Alice Cooper comic book that he pitched unsuccessfully to Marvel Comics. "Rock 'n' roll and comics grew up together," he says. "The comic book came of age around World War II and the 1950s, and rock 'n' roll had its roots in the same kind of culture." His musical and comics tastes ran toward the aggressively funny, and he had no use for such somber, self-conscious music as that of The Doors. "There were funny rock bands before rock 'n' roll became rawk in the '60s and it took itself so seriously. The Beatles could be goofy, but they were never funny. I thought the Damned were always very funny. The Dead Boys were hilarious. There was always an element of humor - to me - to all punk rock."

The Ramones were one of the band that Punk hung its hat on, along with Blondie and The Dictators. Each had a sense of humor, but as the book documents, The Ramones' sense of humor had very definite limits, particularly where they and their careers were concerned. Chris Stein and Debbie Harry from Blondie, on the other hand, were much more game. Harry appeared in both of the fumetti, and Punk helped Blondie work around the artistic hierarchy of CBGB that embraced the high-art leanings of Television and Patti Smith, and the conceptual qualities of The Ramones and Talking Heads.

By John Holmstrom

"The Ramones never copped to being a punk rock band," Holmstrom says, not until the early 1980s. "They always thought they were going to be a legitimate rock 'n' roll band or a pop band. I always thought Blondie handled it well because they didn't care what anybody called them."

The Dictators were a cult band even then, falling in the cracks between generations of punk. Their sense of humor put them squarely in Holmstrom's sweet spot ("I knocked them dead in Dallas / and I didn't pay no dues / I knocked them dead in Dallas / they didn't know we were Jews"), but their flirtation with heavy metal and Handsome Dick Manitoba's wrestler stage patter marked them as theatrical in a way that few CBGB bands were. They were 86'ed from the club and Max's Kansas City after a drunken Manitoba heckled a pilled-up Wayne County, prompting an altercation that ended when County hospitalized Manitoba by hitting him over the head with a mic stand. "They were always doing the wrong thing at the right time," Holmstrom says. They too tried to distance themselves from the punk label, alienating punks with the metal sound of Manifest Destiny and Bloodbrothers. "People did not want the stigma of being a punk band in New York City."

The story of the magazine and its staff - Holmstrom, Eddie "Legs" McNeil, Ged Dunn, photographer Roberta Bayley, and writer Mary Harron - reads much like the biography of one of the bands Punk covered, down to the weird, desperate attempts to stay alive as an entity after the first blush of success. According to Holmstrom, that comparison is fairly accurate. "People always thought of us like a band," he says. "We were John Punk and Legs Punk."

Recently, Holmstrom has been back at CBGB, at least in spirit. The club closed in 2006, but its owner Hilly Kristal and the bar are the subjects of a movie due out this year starring Alan Rickman, Johnny Galecki, Ashley Green, Rupert Grint, Stana Katic, and Malin Ackerman. Director Randall Miller hired Holmstrom to serve as a consultant on the movie. At times, he was spooked by the lengths Miller's crew went to recreate CBGB. On one set visit, he realized that they had the original cash register, the original bar and the original jukebox. "Why can't I get a drink in this bar?" he wondered.