St. Vincent Bowls, The Institute Perplexes, and Alt-Comedy Talks Classic Comedy

Our favorite things this week include St. Vincent videos, ARGs, and "Comedy on Vinyl."

Our favorite things this week include St. Vincent videos, ARGs, and "Comedy on Vinyl."

St. Video: Annie Clark, who performs as St. Vincent, excels at building and controlling her own aesthetic. While touring her latest album, St. Vincent, she emerges onstage as a cult leader with gray-purple hair, high-fashion dresses, and scripted dialogue and choreography. Her aesthetic is precise and powerful. In interviews, she immediately redirects questions about her personal life back to her music. Looking back at her tour videos from the Strange Mercy tour, however, momentarily strips back the mystery. In one, she soundchecks before her 2011 gig at Tipitina's Uptown. It's nothing fancy—no guitar smashing, no crazy tour shenanigans. Clark walks around the venue's main floor, picking out the chords to her song "Neutered Fruit." It's clear that this is a tour ritual she's done a million times before, and she's relaxed but attentive. A few people stand at the bar or back wall and watch in awe, but keep their distance.

Nineteen videos in total chronicle life on tour as members of the band go bowling, talk about their aspirations, and get their hair cut. The videos are quiet, elegant observations of a changing artist. St. Vincent's tour diaries aren't summer blockbuster material, but to see that the metal rocker, the David Byrne collaborator, and the guitar innovator is a normal person is reassuring if unsettling. To see beyond her carefully crafted aesthetic feels like an invasion of privacy, or like finding someone's Facebook posts from middle school. At the same time, the videos show an evolving artist figuring out how to be herself. (Stephanie Chen)

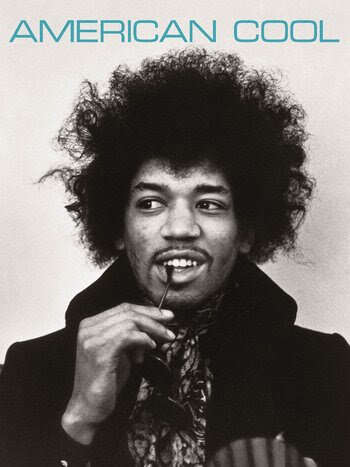

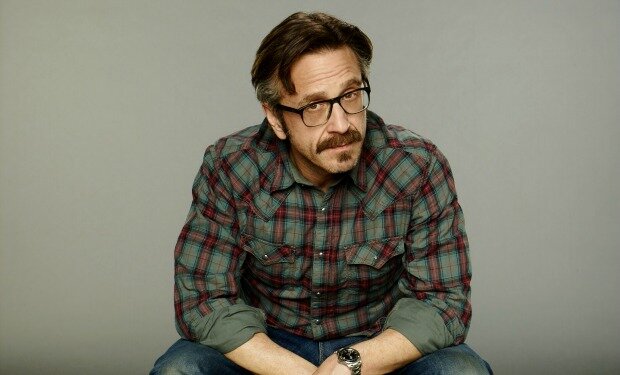

Comedians on Comedy on Record: My first WTF with Marc Maron podcast was the Gallagher episode in 2011, which ended prematurely when Gallagher stormed out, upset over being asked to explain why he did the sort of divisive, old school jokes that now seem hack to be kind, racist and homophobic if you feel less charitable. Since then, Maron has broadened his scope to include actors, musicians, and even the heir to the Dr. Bronner’s Magic Soaps business. While I like a lot of those episodes, I enjoy the comedy shop talk conversations most. Recently I’ve begun listening to Jason Klamm’s Comedy on Vinyl podcast to get my inside comedy fix.

Comedy on Vinyl asks a comedian to select a classic comedy album to talk about, which inevitably leads back to what the comedian does, and often results in the kinds of insights only other comedians have. Brandie Posey talks about ego in stand-up while discussing Billy Connolly’s Big Yin, and Dave Hill talks about “being an idiot” in the episode on Steve Martin’s A Wild and Crazy Guy. The show at its best connects comedians from a very different time and world with alternative comedy today and reveals how their comedy still speaks to us. (Alex Rawls)

What Happened? Many adults long for the nostalgic spark of wonder and imagination that often disappears along with childhood. Alternate reality games, or ARGs help fill that void. In these games, players follow clues and instructions, often delivered through email or phone, in order to solve a mystery that has been laid out by the game’s designer, or “puppetmaster.” Unlike in live action role playing, the players don’t take on pretend identities; instead, the game is integrated into their own lives. This can create a chaotic blurring of reality that is expressed almost tangibly in Spencer McCall’s 2013 documentary The Institute, which streams on Netflix and weaves the tale of the Jejune Institute—an intense alternate reality game that took place in San Francisco from 2008 to 2011 and developed into a cultish phenomenon.

Many ARGs are really little more than extensive interactive advertising campaigns. Indie folk rock band Lord Huron’s songs and videos are based around the works of a mysterious fictitious author. What set the Jejune Institute apart, however, was that it neither marketed a product nor asked for funding from its players. It was meant instead as a social art project. McCall’s film tests the boundaries of documentary style filmmaking, almost adding to the mystery of the game rather than explaining it to the viewer. Ten minutes into the film and it seems straightforward enough, but stick with it and soon you’ll be wondering exactly what in the story is real and what is part of the game—a question that many of the players interviewed seem to have trouble answering for themselves. By creating more questions than answers, the endings of both the game and the film leave their players and viewers somewhat unsatisfied. Still, the film is an endlessly intriguing look into an imaginative alternate reality game that took over and changed the lives of its players. (Lauren Keenan)