The Zombies' Odessey

A cult classic album with a misspelled title was only one adventure for The British Invasion-era band, The Zombies.

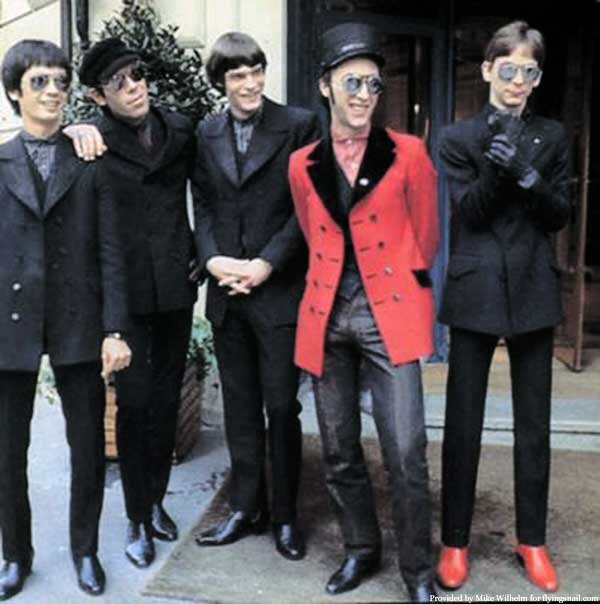

At 19, Colin Blunstone was in a different place from the rest of his community. He lived in southern England in 1964 and had a band he’d formed with friends he’d met in high school in St. Albans. The band, The Zombies, had a hit with “She’s Not There,” and on the strength of its success flew from London to Manchester in the north to appear on “Top of the Pops.” They’d also flown to Oslo for a tour of Norway and the U.S., where they appeared on Murray the K’s Christmas Show in Brooklyn with Dionne Warwick, The Shangri-Las, Chuck Jackson, The Shirelles, and a host of other acts..

Now, thinking about it, he realizes he may have been the only person in his town of 30,000 or so who’d been on a plane at all, much less flown multiple times including a trip to the United States—a hallowed destination at the time.

"Every British musician wanted to play in America," Blunstone says. "America is the home of rock 'n' roll. Our heroes would be Elivs, Chuck Berry, and Little Richard. These were all the people we looked up to. Then you would go back a bit further to the chief guys in rhythm and blues and get back to the blues.

The partly reunited Zombies will play The House of Blues Thursday in a show co-produced by The Ponderosa Stomp Foundation, and Blunstone makes it clear that the British Invasion owed a lot to American R&B. "A lot of the music we played was American music," Blunstone says. "When we came to America, we were playing black American music for white American audiences. I wanted to say, This is your music. I sometimes felt a little bit uncomfortable as if we were pretending that it was ours and we did it first."

When The Zombies first recorded, their sets were dominated by R&B and blues covers, along with perhaps a Beatles song or two—"It might be that we did a cover that they featured and not one of their songs," Blunstone says—but their producer Penn Jones thought it would be a good idea to record something new. Blunstone forgot about his suggestion as the conversation continued, but two days later, keyboard player Rod Argent came in with “She’s Not There,” the band’s first hit.

"We knew right away it was special," Blunstone says. "We had no idea that Rod could write songs." Bassist Chris White wrote a B-side, "You Make Me Feel Good," and they realized they were more than simply a band playing covers.

"She's Not There" made The Zombies part of The British Invasion, and suddenly they went from a band that had played all of its gigs within a 10-mile radius from home to one that played all over the world. Ironically, the British Invasion virtually killed the teenage market in America for the R&B that made the members of The Zombies want to play in the first place. According to Blunstone, the band was so busy playing and touring that the members had little awareness at the time of how revolutionary the time was.

"Probably not as aware as I should have been," Blunstone says. "I didn't feel part of a musical movement. There was a pride that I had. There was a famous worldwide broadcast where different countries showed something of their country. For Britain, The Beatles played "All You Need Is Love" live in Abbey Road [Studios], and I thought, That's really wonderful that this country can produce artists of this calibre. It was breathtaking, and there was a pride I felt that I was from that country. As far as we were concerned, I was more inward-looking about what we were doing and not about whether we were making a contribution to a wider musical picture."

Blunstone thought of rock 'n' roll during that time as a great adventure and didn't have any long term expectations. Rock 'n' roll was still relatively young and nobody had long careers, so he had no expectation that The Zombies or even a career in music would go on forever. He got to be creative and play music he loved, and he saw the world in the process.

During that time, the band released 19 singles in the UK and the U.S. including the hits “Tell Her No” and “Time of the Season,” and two albums—Begin Here (released as The Zombies in the U.S.) in 1965, and Odessey and Oracle in 1968. The former left Blunstone wondering what it could have been like if the band had more time and more experience since it included such commonplace covers as “Roadrunner,” “I Got My Mojo Working,” “Summertime,” and “You’ve Really Got a Hold on Me” next to the handful of songs they had time to write for the session.

"On our first album, there's a song, "Can't Nobody Love You" by Solomon Burke," Blunstone says. "I seem to remember that I found that song on an album I had. I showed it to the band in the morning, and we recorded it in the afternoon. We didn't live with that song at all. We listened to it, played it through a couple of times, and it was on the album. And I think there were a couple of tracks like that."

Odessey and Oracle reflected The Zombies’ growing sense of themselves as artists. Released the same year as The Beatles, Beggar’s Banquet, and The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society, the album reflected a similar sense that an album could be more than simply a collection of prospective singles and filler. Its psychedelic sound has dated in much the same way that The Pretty Things’ S.F. Sorrow—another 1968 release—now does, but it has been seized on over the years as an overlooked classic. Rolling Stone named it number 100 in its list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time, and while that may be generous, it certainly reflects a more musically ambitious band.

"We just wanted to write and record to the best of our abilities," he says. "We wanted to get some sort of artistic fulfillment." But the band's sensibilities weren't as evolved as some fans of the album suggest, and Blunstone cautions against thinking of it as a concept album--something it clearly wasn't in his mind. They did want to produce something that could stand as a work of art, but "those were simply the best 12 songs we had at the time," he says. "We recorded them to the best of our ability, and that's that. We wanted to make something of value."

The process of making the album may color Blunstone's attitude toward it. They were given a 1000 pounds by their label to rmake the album. "I don't know what 1000 pounds would be worth today, but I can assure you it wouldn't be much, particularly if you're recording at Abbey Road," he says. "We had to rehearse everything so that we knew exactly what we were going to do, then we recorded incredibly quickly. There was very little working out arrangements in the studio."

But the album didn’t sell well in its day, but The Zombies had broken up before its release. Keyboard player Al Kooper was an A&R man at Columbia Records when the album came out in England and convinced Columbia to release it, but the band considered itself done.

"In hindsight, perhaps incorrectly, perhaps we felt we'd taken the band as far as we could," Blunstone says. "And we perceived ourselves as being comparatively unsuccessful. The world was a different place, and you didn't know what was happening in other places. We now know that we were together professionally for three years, and we always had a hit record somewhere. But we were tuned in to the UK charts and the American charts, and we didn't know if songs were hits in other countries. I retired at 22--it makes me laugh!"

After they split, Rod Argent went on to have a successful solo career under the name Argent, which had its biggest hit in 1972 with “Hold Your Head Up,” and he transitioned from that into a successful career as a producer. Blunstone had a solo career, then he became a session singer who also sang jingles and songs in films. Neither of them played live for more than 20 years with only the occasonal exception. Then in 1999, he had a chance to play again and asked Argent if he could step in when Blunstone’s keyboard player backed out. Argent agreed and was adamant that he would only do the six concerts that were scheduled, but he enjoyed it so much that he is still playing with Blunstone.

"The original band were professional for three years," Blunstone says. "This incarnation of The Zombies has been professional for 16 years. Very strange, isn't it?"

That experience led to more gigs, and when they discovered how much interest remained in The Zombies. They gradually added more and more Zombies songs to the setlists, and when promoters started using the band name despite being contractually forbidden to, Blunstone and Argent decided to bill their shows as “The Zombies featuring Colin Blunstone and Rod Argent.” The band hasn’t reunited, though bassist Chris White and drummer Hugh Grundy rejoined Blunstone and Argent to perform Odessey and Oracle in its entirety to celebrate the album’s 40th anniversary.

Ironically, Blunstone's musical dream is fairly humble. He'd like to write a standard--a song that doesn't need his voice or face to be successful, something that will have a life of its own and allow him his.

"I never felt comfortable with any degree of fame that I've had," he says. "I've always found it a little bit strange [laughs]. It sounds like I'm complaining, but I'd just as soon be a writer or if I was in film, a director. That sounds a bit grand, a director., but someone behind the scenes and not actually on the screen. That would suit my personality a lot better."