Where's the Audience for New Orleans' Live Music?

Tank and the Bangas at Tipitina’s, by Gus Bennett Jr.

To deal with the wages musicians earn from live music, we first need to address their audiences.

Last month, I offered some thoughts on a social media conversation about musicians’ declining wages at “The Cream,” one of my Substack newsletters. This is a a revised version of that writing.

Last month, Jan Ramsey at OffBeat sounded the alarms, concerned that live music in New Orleans is dying. Musicians can’t make a living wage and the venues aren’t making the kind of money necessary to pay them better. She rightly points out that if musicians can’t make enough to live on, it will affect their ability to keep making the music that New Orleans’ reputation is built on.

Ramsey also rightly calls for those trying to help New Orleans musicians including GNO Inc. to pay attention to live music. In a pre-COVID roundtable that the business development organization hosted, that was a blind spot. People who talk about how to help musicians tend to focus on ways to monetize recorded music, but New Orleans’ reputation is built in large part on live music. Many musicians whose incomes are declining don’t write their own songs, or their music really lives in the moment onstage, and they only really record and sell their music as souvenirs. Idea Village has a new music industry accelerator program, Metronome, but if it doesn’t consider live music, it will leave out an important sector of the New Orleans music community.

But thinking about who has sufficiently deep pockets to help bail out the musicians is a shaky proposal. Trying to get the beer and liquor industry that benefits from having its products sold in clubs to pay is a novel idea, but what if they say no? Are we going to prohibit bars from promoting shows or selling beer? Try to stop venues from selling beer? Is that possible, much less desirable?

The proposal that City Hall could create incentives for venues to make greater commitments to live music and the musicians is intriguing, but New Orleans’ history of erratic, occasional action on noise and zoning violations doesn’t give me much hope for that idea. The details on how we measure a club’s commitment are one obstacle, and defining what kind of live music gets love is another. The problem on Frenchmen and Bourbon streets isn’t the lack of live music; it’s the lack of live music that we’d recommend to our friends. I think of much of it as cynical, only as good as it has to be to get people in the bar to buy a drink. In a city built on versions of “Hey Pocky-Way” where some of our biggest stars are interpreters of music, who wants to tackle the job of determining which live music merits tax breaks and which doesn’t?

While we look for who can save New Orleans’ clubs and musicians, it’s helpful to think about the core of the problem: Not enough people are coming to see New Orleans’ musicians in the clubs. When I served as music editor at Gambit, I spitballed that maybe three percent of New Orleanians were seeing live music on any given night. It was a guess, but far more people don’t see live music than do, and national acts get a lot of that business. Whatever the exact number is, it’s disappointing, and Job One needs to be to grow that audience. NOLAxNOLA is working on that on the special event level, but one thing City Hall can do is make the domestic audience part of the city’s marketing strategy. We need tourists to see our musicians, but we need New Orleanians to see them too.

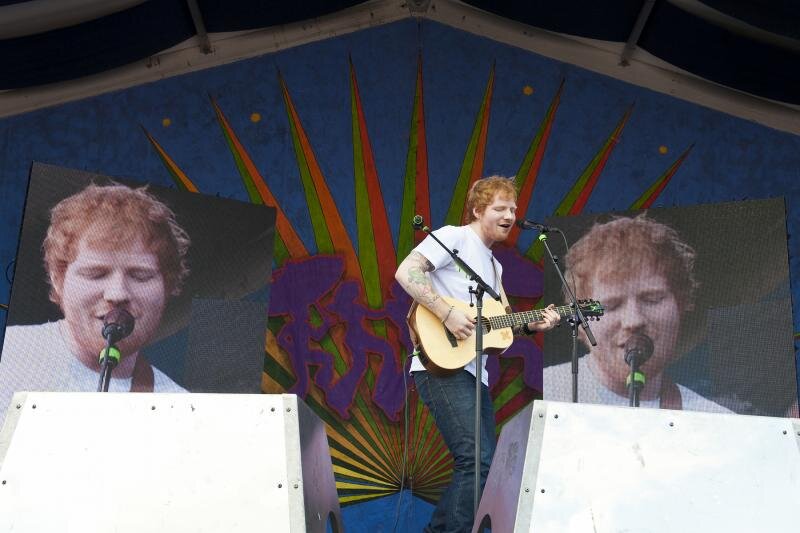

It’s also useful to think about which clubs that book local music—in whole or part—have a clear, distinctive booking policy and a vibe. Who’s running a venue that people want to hang out at to see what’s going on or who’s there? Tipitina’s and the Maple Leaf may be institutions, but they’re institutions with fairly clear compasses. They’re still places that people who want to hear live music can drop into and have a decent idea what they’re going to get.

Chickie Wah Wah with its current bookers is moving in that direction. Gasa Gasa, Dragon’s Den, Spotted Cat, BJ’s, and Santos speak to specific audiences. I’m sure I’m forgetting some, but there are also venues whose listings are so safe or nondescript that its hard to imagine how the bookers and the customers are having much fun.

Some of these thoughts are inspired by a recent conversation I had with Mark Cline and Armistead Wellford of Love Tractor. We talked about why Athens was a hotbed of creative music in the early 1980s when they played with R.E.M., Pylon, The B-52s and The Method Actors, and one of the takeaways was that it was a scene, and musicians saw each other play. Because of that, there was an audience that got them, and that was crucial to their development.

I don’t think it’s reasonable to expect musicians to now add to the number of nights out on their calendar and go to other shows, but when the Circle Bar was happening in the early 2000s, it was a clubhouse for musicians as much as a bar or venue. When Frenchmen Street made its reputation in the ‘90s as the place where real music lived in New Orleans, musicians showed up because they understandably wanted to be where the action was.

Those scenes happened organically in the same way that the Athens scene did, and it’s useful to note that the clubs weren’t booked with tourists in mind or counting on tourists to help make the nightly nut. In New Orleans during better days, tourists showed up because they wanted to see what was happening, but the gigs were booked for the audience that would get them. If out-of-towners turned up too, all the better. In a tourism economy, it’s hard not to look for the tourists, but perhaps a greater focus on the hometown audience would be more useful.

There’s a lot to chew on in this issue. I wonder, for example, if we’re seeing the New Orleans manifestation of a national phenomenon. Young people who would have been live music audiences in the past are going to dance clubs now. I also wonder if New Orleans’ clubs book for more mature audiences too much. The audience has been New Orleans’ secret sauce for years, showing up reliably not only for days at Jazz Fest but to see local bands in bars. That’s an audience that doesn’t always exist in significant numbers in other cities, and it’s an easy audience to book for because it has a decades-long track record to show bookers who they’ll see. At times though, I wonder if venues are focusing on that audience and, foregoing the younger audience, which is less predictable but historically the one most likely and most able to spend late nights seeing live music. It’s also the audience that will grow up to become mature audiences. If we don’t cultivate a younger audience for live music now, we may not have either audience in meaningful numbers in the future.

I get where Ramsey is coming from. When New Orleans chose to focus on tourism its economic engine, it put the city’s financial future in large part on the back of its musicians. It now seems like the city could help when many musicians can’t afford to live in Orleans Parish.

That’s a valid concern because it’s grossly unfair. New Orleans can’t claim to be a musician-friendly city and separate the reality of musicians’ lives from the music that they make. But it’s also true that successful businesses—including musicians and venues—think about their audiences, and maybe the clubs and musicians would benefit from thinking a little more precisely about its relationship with its live music audience.

Creator of My Spilt Milk and its spin-off Christmas music website and podcast, TwelveSongsOfChristmas.com.