"Can't Slow Down" Makes the Case for 1984

Writer Michaelangelo Matos tells the story of a year in a sneered-at decade to defend its reputation.

Purple Rain. Wham! Tina Turner’s Private Dancer. She’s So Unusual. Bronkski Beat. PMRC. Like a Virgin. Compact Discs. Van Halen’s Jump. Stop Making Sense. Bob Marley’s Legend. Zen Arcade. R.E.M.’s Reckoning. Los Lobos’ How Will the Wolf Survive? Run-DMC’s “It’s Like That.” Yes’ “Owner of a Lonely Heart.” “ Ghostbusters.” Marvin Gaye’s National Anthem before the NBA All-Star Game. MTV’s Video Music Awards. ZZ Top’s “Legs.” Foreigner’s “I Want to Know What Love Is.”

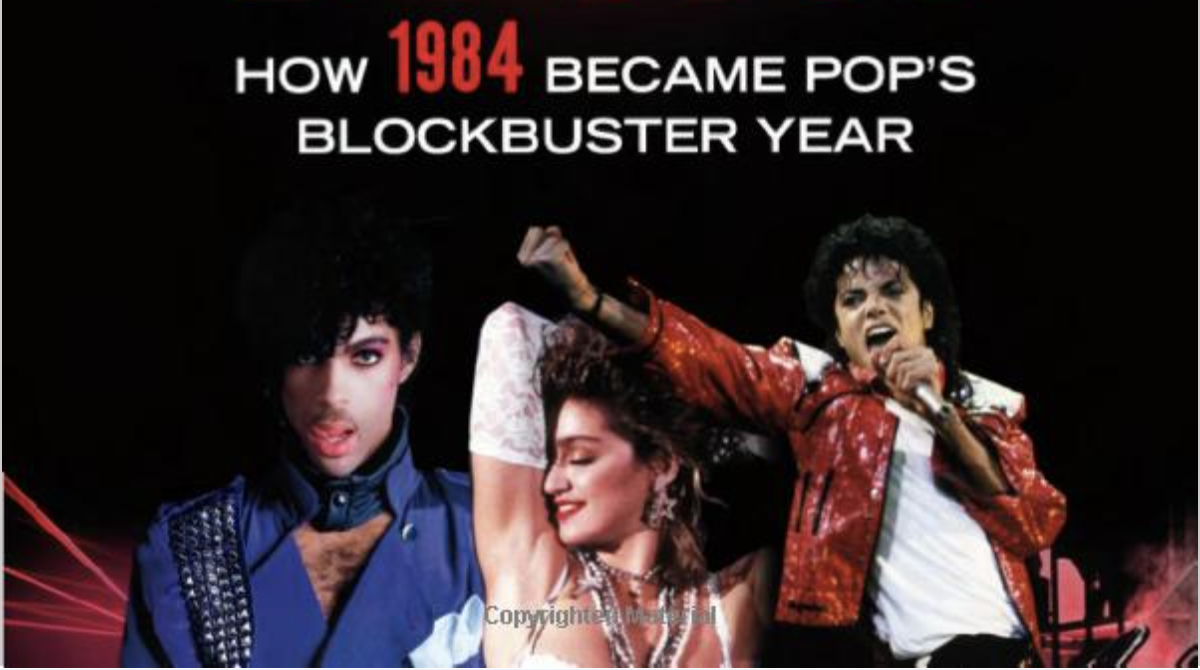

A lot happened in 1984, and music critic and journalist Michaelangelo Matos fits all of them and more into Can’t Slow Down: How 1984 Became Pop’s Blockbuster Year. The book functions in part like a yearbook, checking in on what happened that year, giving at least a few paragraphs to almost anybody who mattered, but he lets the accumulated details coalesce into a larger argument for the significance of the year.

Matos first thought about writing a book about 1984 in 2009, but he wasn’t really ready for the project at the time and nothing came of it. In 2015, he wrote The Underground is Massive: How Electronic Dance Music Conquered America (and spoke to My Spilt Milk at the time), After turning in that manuscript, Rolling Stone asked him to contribute to its list of top albums from 1984, and when that list was published, his friend and fellow critic Jody Rosen texted him, Weren’t you going to do a book about that?

“The minute I saw him say that, I knew, Yeah, that’s what you have to do,” Matos says in an interview with My Spilt Milk.

In the 1980s, the dominant critical mode in America was rockist, which put guys—generally—with guitars who play rock, not pop, in the forefront, and album artists with lengthy track records at the head of that pack. It was the lens through which Rolling Stone has told the history of rock ’n’ roll, and that lens made some sense that year. In Matos’ telling of 1984’s story, the bar band stands as the emblem of the American work ethic. “In that way, it was very Reaganesque,” Matos said. “That was concurrent through Bruce Springsteen and the American underground. That’s every Peter Buck interview.”

Springsteen’s 1984 stood as a parable of virtue rewarded, American style. The years of effort he put in on his career, the marathon shows, and the obvious hours he logged in the gym paid off with stadium-level success with Born in the USA in 1984. Even though Prince didn’t have the guns Bruce showed off in the “Dancing in the Dark” video, critics and the record-buying public similarly cosigned the decade of work he put in leading to Purple Rain as well.

But as Can’t Slow Down shows, championing guys with guitars had serious limitations. That framework left some of the most impactful artists and developments out of the year. Madonna, for instance, was dismissed by critics as someone with more ambition than talent. They credited the success of the singles from her debut album to the producers she dated, not her. Although her label head Seymour Stein wrote in his autobiography, “Madonna was always the smartest person in the room, even when she wasn’t physically there,” she didn’t get credit for masterminding her success until 1985 and the release of the movie Desperately Seeking Susan. Her skill in an acting role allowed critics to finally recognize the decisions she had made in her career to that point as choices and not simply extensions of her love life.

Matos says that approach similarly undervalued the British new wave acts that started to transform popular music, even before it became an actual market force in America. “Brits were seen as pop,” Matos says. “They were seen as fun trick noisemakers that exploded and disappeared.” He pays attention to Frankie Goes to Hollywood in the book, drawing attention to the efforts of producer Trevor Horn and former NME writer Paul Morley to position Frankie as the epitome of pop. Matos quotes Horn in Can’t Slow Down as saying of Frankie’s first hit, “Relax,” “I’m sure I’m not denigrating it in any way by saying that it was an advertising jingle, and a brilliant one.”

English fans had always been more accepting of pop and its fabricated nature, but American audiences have generally needed to believe in the artist’s talent, not just the song. For that reason, British pop stars that topped the charts in England were slow to catch on in the States. One of the vehicles that helped American audiences embrace new wave was the video, in part because of the new, stylish nature of the videos themselves, but also because of the contexts they inhabited. Matos writes about the growth of rock discos—dance clubs that featured rock music with dance rhythms, much of which came from England. Bands including Duran Duran and Spandau Ballet were initially processed in America as points on the funk spectrum because of those rhythms, and since those videos were shown in these clubs, they took on an underground frisson that is hard to imagine today.

They also stood out on MTV, and 1984 was a transitional year for the network. It was only three years old and was still trying to get cable companies around the country to pick it up. It in effect commissioned the “Thriller” video that became so popular the channel promoted upcoming showings on the air. Videos had yet to become an automatic part of an album’s promotion, so MTV surrounded Jackson’s videos, and those by Culture Club, Wham! and the other British new wave acts with the established album-oriented rock stars that chose to make videos anyway. Their age and desperation to stay in the marketplace only made the young bands seem fresher. In Can’t Slow Down, Matos writes about the unease and resentment with which Eagles Glenn Frey and Don Henley entered the video realm, and how ZZ Top found a new chapter in their career by doubling down on their hairy, dusty age.

“Duran Duran stood out from Rod Stewart on MTV,” Matos says. “That was a big part of the acceleration of the boomer trajectory downward through the ‘80s. They couldn’t hack MTV.”

That generational divide is a line that dots through the book. He doesn’t explicitly argue that 1984 should be thought of as a rival for some of the most storied years in music history, but by presenting the amount of consequential activity that took place that year, he leads readers to that conclusion. That was intentional. “1984 didn’t have the rock mythos of 1977 or 1964,” he says, and he subtly redresses that issue by presenting the old boys’ activities as well. He depicts The Jacksons’ Victory Tour as a dinosaur walking as the family tried to cash in on Michael’s Thriller success. Matos follows his story into 1985 and Live Aid, where American promoter Bill Graham did his best to marginalize younger acts and stacked the lineup at the concert in Philadelphia with the rock pantheon of the ‘60s and ‘70s, including Bob Dylan, Neil Young, Eric Clapton, Led Zeppelin, and Crosby, Stills & Nash. Joan Baez announced early in the day, “Children of the ’80s—this is your Woodstock,” and the cumulative effect of sentiments like that and the lineup itself made it look like they were trying to make an event started by post-punk and new wave artists all about them.

The American media including MTV played along—“The boomer-controlled media had its own bacon to fry,” Matos says—but that linkage seemed wrong immediately. The sound and style of pop music in the early ’80s were inspired by the future, not a wistful look back at the past. Synthesizers presented a world of sounds that couldn’t be created by conventional instruments, and drum programming allowed rhythm possibilities beyond human capacities. Fans of then-current pop didn’t look back to the ’60s to see a music revolution; they saw it in the birth of punk not 10 years in the past. They were living a moment that pushed the frontiers of technology and pop while hip-hop changed even the idea of the song.

“That is a reason that era is so ill-remembered,” Matos says. “It’s not a heroic era for the great rock icons. In fact, it’s an anti-heroic era, which made it great fun to write about.”

Michaelangelo Matos talked about Band Aid’s “Do They Know it’s Christmas” and Wham!’s “This Christmas” from 1984 on our Christmas music podcast, The Twelve Songs of Christmas.

Creator of My Spilt Milk and its spin-off Christmas music website and podcast, TwelveSongsOfChristmas.com.