Shoes Like New Again

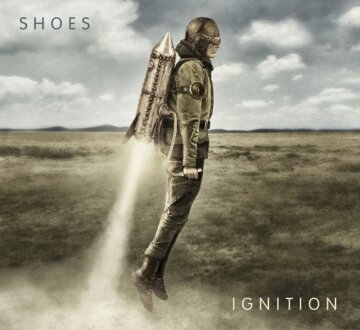

Time tested Shoes, but the band's brand of power pop sounds timeless on "Ignition."

This is a story from a moment that never existed. In the mid-1970s, power pop seemed like a great idea, combining a love of pure pop starting but hardly ending with The Beatles with the crunch of then-contemporary rock ‘n’ roll. But when Dwight Twilley Band’s classic Sincerely came out in 1976, Elton John and Kiki Dee topped the charts with “Don’t Go Breaking My Heart,” and Rhythm Heritage made the Top 10 with “The Theme from S.W.A.T.” The closest thing to power pop in the Top 10 was the syrupy ballad “All By Myself” by Eric Carmen, formerly of The Raspberries.

1977 wasn’t much more hospitable. A Gallup poll determined Kiss to be the most popular band in the land, more or less as Kiss Alive proclaimed, and Casablanca Records released Donna Summer’s “I Feel Love.” Saturday Night Fever was released, David Bowie appeared on a Christmas special with Bing Crosby, and Pink Floyd toured stadiums on the Animals tour with a giant, inflatable pig. Not exactly the zeitgeist that would seem right for the modest Black Vinyl Shoes by Zion, Illinois’ Shoes.

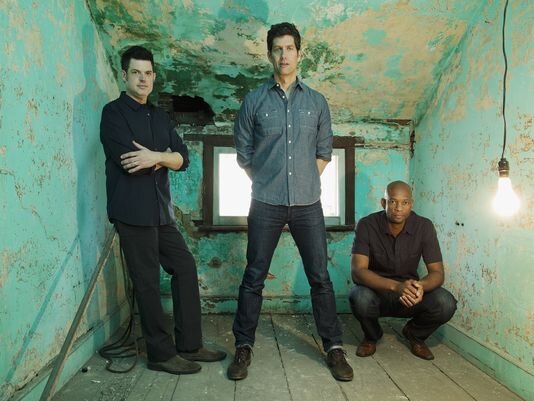

Shoes--Jeff Murphy, John Murphy and Gary Klebe--return today with the excellent Ignition, an album that retains the charms of the best Shoes songs: smart, unpredictable hooks, great melodies and harmonies, and as the lead track “Head vs. Heart” demonstrates, a wiry tension gives the songs urgency. They never actually split, but they’ve been on the sort of extended hiatus that’s easily mistaken for a break-up.

“In the long run, how many people in rock n roll end up happy?” Gary Klebe asks. “I mean, there’s happy memories, but even those who are at the top of their game for as long as they can still wish for the early times, wish they had number one hits. Paul McCartney, The Rolling Stones, or whatever, I think there’s still a yearning for better times, and these are people that are immensely successful. Then there’s all the rest of them that had record deals for a while and now they’re gone and now the money’s gone, the attention, stardom. It’s hard to come out on top in the end. You just have to appreciate the good times you had.”

Klebe doesn’t sound that down on the rock ‘n’ roll experience speaking by phone from his home in Zion, where he and the Murphy brothers still live and work. He’s “done some architecture” and works in a catalog company with John Murphy, and he’s practical--a hallmark of the band from the start. They weren’t a high school garage band that were trying to get girls and live rock star dreams. They just loved rock ‘n’ roll.

“It’s our only band,” Klebe says. “It is our first band. We pretty much learned to play together. We knew a few chords and we were embarrassed to play in front of other people, much less ourselves.We were just beginners. The concept really started back in college when we talked about how cool it’d be to start a band because we were such music fans. We came up with the name Shoes and said, ‘Well, I guess we better learned our instruments.’ Next thing you know, we each know two or three chords and we’re starting to write crude songs. We developed pretty fast because we had a major label contract within probably three or four years from the time we got out of college.”

Instead of working songs out live in a garage, Shoes recorded them in the basement on a four-track tape machine that allowed them to build the tracks part by part. Live performance was never the band’s priority, Klebe says, and it certainly wasn’t at the start. “Many friends were very good musicians and had been in bands for a long time,” he says. “So we were kind of embarrassed to even say we were doing music. We didn’t want to be laughed at. We were just beginners at the time. The recording was the only way we could slip in and come into the whole thing through the back door.”

Still, their independently recorded and released Black Vinyl Shoes album did well enough that PVC Records licensed it in the United States and Sire licensed it in the UK. Shoes’ musical identity was already clear, and times, trends and haircuts can change--check the cover of 1989’s Stolen Wishes--but the songs remain the same.

“A lot of people don’t believe it when I say this, but we barely can play anything by anybody else,” Klebe says..” We had to learn a few cover songs when we first started playing live, but we never really formally learned things, never learned how to play Led Zeppelin leads and really fancy things. We invented our own language, our own way of getting the idea down.”

Their way of doing things got them signed to a three-album deal with Elektra Records, and while power pop wasn’t of a piece with punk and new wave, it was music on a similar scale and with a similar love of the three-minute song. Shoes were also D.I.Y. before D.I.Y. existed and certainly indie before indie, so there was aesthetic overlap. Elektra certainly saw similarities. The label saw the platinum success of The Cars’ debut album and figured a band like Shoes could be bigger.

“When we got back from recording our first record [Present Tense] in England, our expectations were, ‘Wouldn’t it be great if we could sell 25,000 records?’ They hear it and they love the record. The label says they expect 3 or 4 million minimum, and we were completely shocked. They almost liked it too much.”

The album had a classic Shoes track, “Tomorrow Night,” but one of the problems according to Klebe was the label’s inability to pick a single and focus on it. Elektra released “Tomorrow Night” and three other tracks without committing promotional muscle to any of them. “Everyone was so successful that almost no one was actually willing to develop talent,” Klebe says. “Right out of the gates, if it wasn’t platinum, forget about it. Elektra was rolling, and when someone like us comes along, 100,000 sales is considered to be a failure. Now, that’s a hell of a lot of records. When it sold, it did pretty well, way better than we ever thought it would do, but nowhere near what was expected. ”

Every label had a power pop band, though the genre’s commercial breakthrough started and finished with one song: “My Sharona.” Power pop aficionados have something more elegant in mind when they think of the term, but it had power, it was pop, and it was huge. The band’s wardrobe nodded to The Beatles and Stones, and when The Knack didn’t produce another song that big, “My Sharona” and power pop bands were dismissed as novelties. Shoes weren’t helped by the implosion that was taking place at Elektra. “Around 1980, Warner Bros came in and basically fired all of Elektra, shut down the building, moved to a new operation at Elektra with new people. They were on top, and that’s how quickly it can turn around. And we were right there up to a third record. We witnessed everything.”

1977 wasn’t much more hospitable. A Gallup poll determined Kiss to be the most popular band in the land, more or less as Kiss Alive proclaimed, and Casablanca Records released Donna Summer’s “I Feel Love.” Saturday Night Fever was released, David Bowie appeared on a Christmas special with Bing Crosby, and Pink Floyd toured stadiums on the Animals tour with a giant, inflatable pig. Not exactly the zeitgeist that would seem right for the modest Black Vinyl Shoes by Zion, Illinois’ Shoes.

Shoes--Jeff Murphy, John Murphy and Gary Klebe--return today with the excellent Ignition, an album that retains the charms of the best Shoes songs: smart, unpredictable hooks, great melodies and harmonies, and as the lead track “Head vs. Heart” demonstrates, a wiry tension gives the songs urgency. They never actually split, but they’ve been on the sort of extended hiatus that’s easily mistaken for a break-up.

“In the long run, how many people in rock n roll end up happy?” Gary Klebe asks. “I mean, there’s happy memories, but even those who are at the top of their game for as long as they can still wish for the early times, wish they had number one hits. Paul McCartney, The Rolling Stones, or whatever, I think there’s still a yearning for better times, and these are people that are immensely successful. Then there’s all the rest of them that had record deals for a while and now they’re gone and now the money’s gone, the attention, stardom. It’s hard to come out on top in the end. You just have to appreciate the good times you had.”

Klebe doesn’t sound that down on the rock ‘n’ roll experience speaking by phone from his home in Zion, where he and the Murphy brothers still live and work. He’s “done some architecture” and works in a catalog company with John Murphy, and he’s practical--a hallmark of the band from the start. They weren’t a high school garage band that were trying to get girls and live rock star dreams. They just loved rock ‘n’ roll.

“It’s our only band,” Klebe says. “It is our first band. We pretty much learned to play together. We knew a few chords and we were embarrassed to play in front of other people, much less ourselves.We were just beginners. The concept really started back in college when we talked about how cool it’d be to start a band because we were such music fans. We came up with the name Shoes and said, ‘Well, I guess we better learned our instruments.’ Next thing you know, we each know two or three chords and we’re starting to write crude songs. We developed pretty fast because we had a major label contract within probably three or four years from the time we got out of college.”

Instead of working songs out live in a garage, Shoes recorded them in the basement on a four-track tape machine that allowed them to build the tracks part by part. Live performance was never the band’s priority, Klebe says, and it certainly wasn’t at the start. “Many friends were very good musicians and had been in bands for a long time,” he says. “So we were kind of embarrassed to even say we were doing music. We didn’t want to be laughed at. We were just beginners at the time. The recording was the only way we could slip in and come into the whole thing through the back door.”

Still, their independently recorded and released Black Vinyl Shoes album did well enough that PVC Records licensed it in the United States and Sire licensed it in the UK. Shoes’ musical identity was already clear, and times, trends and haircuts can change--check the cover of 1989’s Stolen Wishes--but the songs remain the same.

“A lot of people don’t believe it when I say this, but we barely can play anything by anybody else,” Klebe says..” We had to learn a few cover songs when we first started playing live, but we never really formally learned things, never learned how to play Led Zeppelin leads and really fancy things. We invented our own language, our own way of getting the idea down.”

Their way of doing things got them signed to a three-album deal with Elektra Records, and while power pop wasn’t of a piece with punk and new wave, it was music on a similar scale and with a similar love of the three-minute song. Shoes were also D.I.Y. before D.I.Y. existed and certainly indie before indie, so there was aesthetic overlap. Elektra certainly saw similarities. The label saw the platinum success of The Cars’ debut album and figured a band like Shoes could be bigger.

“When we got back from recording our first record [Present Tense] in England, our expectations were, ‘Wouldn’t it be great if we could sell 25,000 records?’ They hear it and they love the record. The label says they expect 3 or 4 million minimum, and we were completely shocked. They almost liked it too much.”

The album had a classic Shoes track, “Tomorrow Night,” but one of the problems according to Klebe was the label’s inability to pick a single and focus on it. Elektra released “Tomorrow Night” and three other tracks without committing promotional muscle to any of them. “Everyone was so successful that almost no one was actually willing to develop talent,” Klebe says. “Right out of the gates, if it wasn’t platinum, forget about it. Elektra was rolling, and when someone like us comes along, 100,000 sales is considered to be a failure. Now, that’s a hell of a lot of records. When it sold, it did pretty well, way better than we ever thought it would do, but nowhere near what was expected. ”

Every label had a power pop band, though the genre’s commercial breakthrough started and finished with one song: “My Sharona.” Power pop aficionados have something more elegant in mind when they think of the term, but it had power, it was pop, and it was huge. The band’s wardrobe nodded to The Beatles and Stones, and when The Knack didn’t produce another song that big, “My Sharona” and power pop bands were dismissed as novelties. Shoes weren’t helped by the implosion that was taking place at Elektra. “Around 1980, Warner Bros came in and basically fired all of Elektra, shut down the building, moved to a new operation at Elektra with new people. They were on top, and that’s how quickly it can turn around. And we were right there up to a third record. We witnessed everything.”

The Elektra experience was discouraging and left the band with no other label interest. Shoes got back to what they knew how to do--record. “A lot of bands would say, ‘We’re going to go on the road and build a following again and really catalyze what Elektra did,’” Klebe says. “Our instincts were, ‘Gotta build a studio.’ Had to have that studio. Need that workshop.” And that began the next phase of their musical career, one far longer than the start. They recorded some music for their own Black Vinyl Records label, put out a greatest hits CD, and slowly morphed into a studio and a distribution business. Kiss’ Gene Simmons was a fan and briefly talked with the band about recording for his proposed Simmons Records, but that fell through. For a while, the business worked but by 2000, digital recording had lowballed their studio out of existence, and changes in the industry killed their distribution business. At that point, the bitter irony kicked in that the activity that they’d taken on to finance Shoes had pushed Shoes to the back burner, and it still didn’t work. Feeling defeated, they closed the studio, got out of distribution and took some time off. “It took a long time to heal from it,” Klebe says. “We have a lot of scars from all that time.”

Not so many that he couldn’t imagine recording again, though. When Klebe got the house he now lives in, he built a studio in it without telling the Murphy brothers. “I didn’t know how they would react to it,” he says. “I was hoping that Shoes could use it and we’d make another record or two.” In 2010, they started working together again. Jeff Murphy had a song, “Out of Round,” and Klebe had “Nobody to Blame,” both of which appear on Ignition. The first efforts were tentative and unusual as Murphy showed them his song instead of demoing first. At first, they moved hesitantly, not sure how to proceed, but before long, Klebe started adding parts and John Murphy began editing the track, even changing the beat. That process went well enough that they kept at it and on New Year’s Day 2011, they solidified four tracks and knew that they were working again.

The release of Ignition will be followed up by an extensive reissue series by the Numero Group and the publication of Boys Don’t Lie: A History of Shoes by Mary E. Donnelly. “It really started off as a fantasy,” Klebe says. “We talked about this imaginary band before we could play instruments. We didn’t even know if we could make music, if we could write songs or perform. But we learned, inch by inch, how to do it. It was really lovely music in the beginning. We started as fans; this isn’t some case where we’re taking guitar lessons since the age of six years old. We didn’t start until many, many years later, but only to follow the idea that we wanted to make records. To do so, we had to learn to play instruments.”

Alex Rawls